On a wall edging a Bogotá, Colombia, street, music and theater posters vie with fight cards and bullfight notices pasted cheek-by-jowl to a rough, stucco wall. Over them are stenciled images of balaclava-clad guerrillas and the scrawled brigade name, M19, alternating with random graffiti, the surface peeling open like a looted archeological site. Walker Evans might have photographed it in small-town America while working for the WPA, but this vivid reconstruction, made of cement and paper ephemera hand-collected at the source, was painted by Layne Meacham for exhibition at the Howa Gallery, where it and others like it will share space with the enigmatically evocative assemblages of Frank McEntire.

There is something wonderfully apt about Thomas Howa locating his gallery just beyond Salt Lake’s boundary, so that departure is required along a brief stretch of open road, so like crossing open water, into another place and an altered state of mind. Like sailing to an island, a 10-minute drive offers an appropriate place to encounter McEntire and Meacham, travelers returned from afar to report their disparate encounters. Meacham’s journey was literal, to the Andes Mountains and the City of Bogotá, where he observed what less attentive travelers overlook—literally the handwriting on the wall—after which he performed the aesthetic equivalent of carving out choice excerpts and bringing them back like trophies to share with his curious kinsmen. McEntire’s ongoing pilgrimage took him across less material dimensions, to a metaphorical mountaintop whence he could survey humanity, seen from a perspective permitting preternatural understanding of what he saw, and then on his way down to gather up cast off fragments, the detritus of human industry that he could assemble into perceptual signs and icons of deep significance. Like the legendary generals of Republican Rome, who were required to bivouac their armies beyond the Rubicon before entering the city, these artists have set down their visions just beyond the salty verge, at a safe distance and in a neutral space, where their eye-opening insights can be safely viewed before the shutters of the mind close again, leaving it to a handful of daring collectors to bring back portions of what they saw.

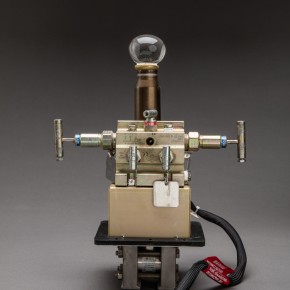

“Stupa for the Last Dark Drop,” an elegant sculpture of Frank McEntire’s, consists of a half-dozen cylindrical elements set one atop another. A Doric column ascends from a pedestal to support a drum, roughly carved from gray stone, capped by a machine-turned and polished metal pedestal that finally supports an oil can under a glass bell. As a visual narrative, it encapsulates the story of human enterprise from a single, skewed point of view, recalling the geologic nature and cultural consequences of petroleum in a fashion that foregrounds the irony of scale: so much fuss just to make a drop of oil a king. It’s part of McEntire’s skill to make the most generic devices appear custom-created to perform the tasks he sets them. Spring clips gently cradle a pebble in which a crystal has been embedded; chemical lab-stands spring up organic festoons; controls reverse their roles to send out signals instead. On a rotating stand meant to hold and flip an hourglass, two pocket-sized deities await alternating turns like children on a see-saw. And in a pair of elaborate reliquaries, iconic fast foods are celebrated by scuffed effigies, one of a water-dweller and another of a mighty vessel plowing the ocean’s waves.

There are 10 paintings by Layne Meacham, six of which celebrate the vitality of Colombian street life. “Maria Cano Viva” (Maria Cano Lives) features a graffito celebrating the first woman to assume a leadership role in Colombia. “Armenia,” invokes Che Guevara, “Camilo” expresses a debt to the liberation theologist Father Camilo Torres Restrepo, while “Serrar Hospitales es Terrismo” (To Close Hospitals is Terrorism) expresses the conviction that health care is a human right. While each of these panels foregrounds a political statement, they do so as part of an unusually complete picture of popular life in a country where politics plays a far more volatile role than here in the United States, where televised squabbles of celebrity candidates substitutes for a debate over policies few seem to care about. Under these circumstances, even an abstract botanical image of a “Verdigerous Lily” begins to resemble a falling bomb. As though to dissolve the illusion that his Utah neighbors have little in common with Colombians, the folk mural “Embera Native on the Darien River” manages to suggest a very different context, that of an outdoor adventurer plying a kayak, while “Shooting the Tube at Suicide Rock” celebrates the artists own, very different aquatic experience.

Frank McEntire’s art may be harder to translate into words, if only because his references are broader, his judgments more personally felt, and more incisively expressed. Of course McEntire has long been viewed in Utah as a religious artist, a case of context and popular interest coinciding with the general demeanor, if not the specific content, of an artist’s works. He may use a religious reference to comment on the role of secular matters in society (the stupa mentioned above is a Buddhist reliquary building that doubles as a place of meditation), or a secular relic may comment on the state of religion, as happened with his notorious (and censored) vending machines that dispensed sacred charms. Because he likes to assemble his art with objects that come ready equipped with powerful associations, he often makes sacred references the way a musician might use a loud chord as a way of making sure he has the audience’s attention. It wouldn’t be true to say his art never concerns the sacred: just that spiritual content should not be taken for granted simply on account of his employing images from religious contexts.

Both these artists are seasoned hands, local heroes of a certain age who could be coasting on their laurels, as many artists do once they’ve established a reliable approach to occasionally changing subjects, or a topic that consistently pleases an audience. But instead, they take chances and insist on bringing something new and big to each new exhibition. Aside from the danger of frequenting slums and barrios, Layne Meacham runs a professional risk exemplified by the Colombian collector who excoriated him for “showing the worst of my country.” The panels he produces are both heavy and fragile, but along with their superb color compositions and simultaneous possession of energetic motion and compound balance, they really do bring a fresh perspective and an exciting, globe-trotting awareness of life in the wider world to anyone in their presence.

Frank McEntire, meanwhile, continues to strive toward a challenging equilibrium: one that balances clarity of vision against the aesthetic qualities of modesty and reverence. As a writer may strive for a perfect sentence, a musician a perfect chord, McEntire would combine the manufactured and the natural—the man-made and the god-made, so to speak—in a harmony that illuminates not only what its like to be alive in this moment and place, but what it means to be at all, whether as a stone or a chair in “Finding,” a beehive atop an industrial assembly for “New Beginnings,” or “Lazarus” risen from the grave. Under his influence, identity and physical form may fall haphazardly into sync, or they may have to be brought into alignment by art, but when it happens, a kind of perfection—or holiness—emerges, as if some cosmic batteries had been switched on and were supplying energy through the thick cable extending from the “Disambiguation Device for the Age of Kali Yuga.” When that happens, the work becomes a conduit from a higher state of being; not a reason to feel superior, but a way to know what superiority must be like.

Aftershocks North of Beck Street, an exhibition of works by Layne Meacham and Frank McEntire, opens at Howa Gallery in Bountiful (390 N. 500 West) on Friday, Nov. 13th, 6-9 p.m. and continues through Dec. 5.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts