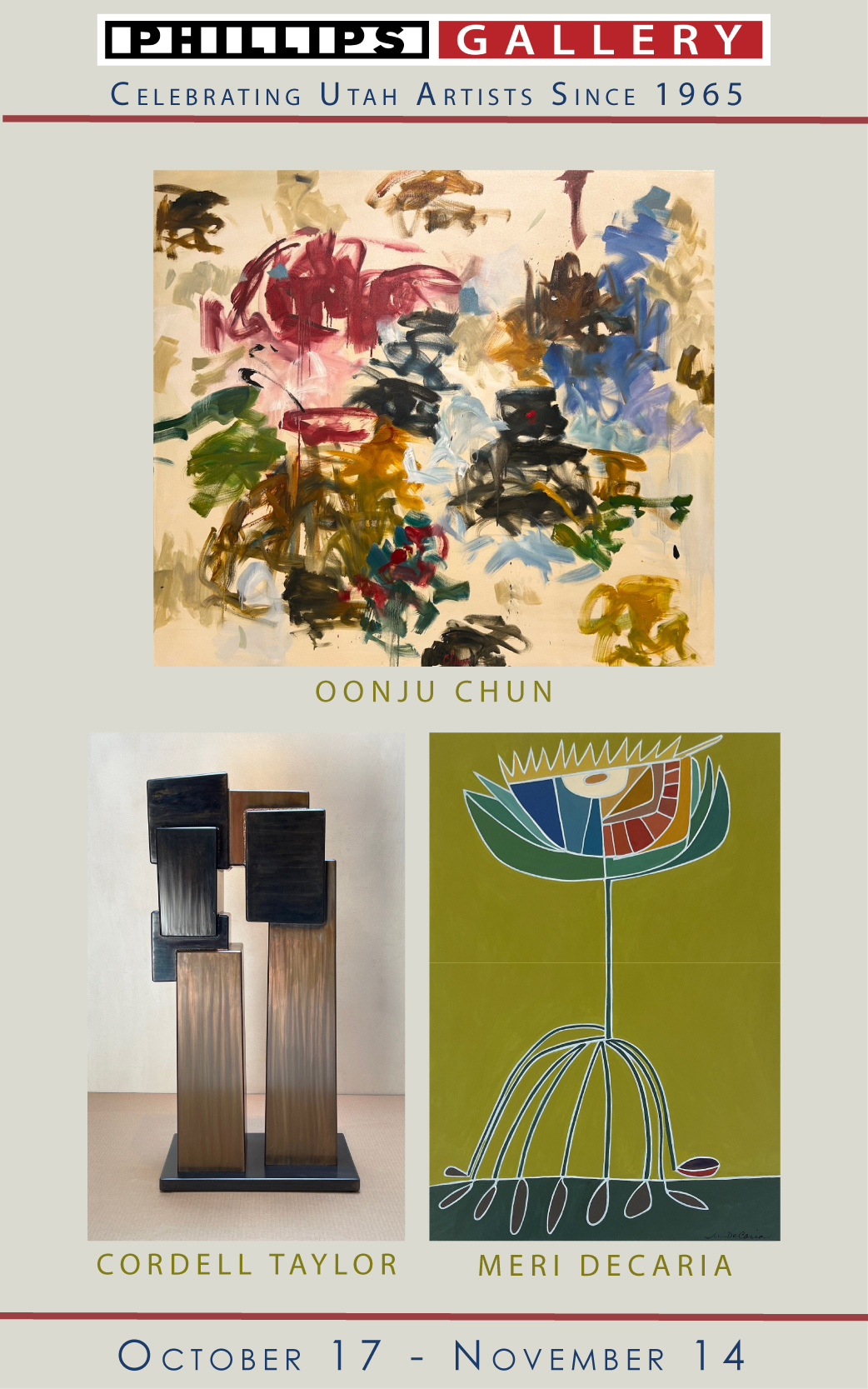

Jason Walker at work in his Cedar City studio, painting a ceramic vessel with intricate underglaze drawings that blend natural and industrial imagery. Image by Shawn Rossiter.

If you happened to have visited The True and the Real exhibition at UMOCA during the NCECA annual conference back in March, you probably came across Jason Walker’s “Trophic Cascade.” The sculpture presents a jaguar poised to launch at its prey from a tree hybridized with civic sewer works. Its stare fixes your gaze. You are dinner. Piping that should belong to that industrialized tree instead wends its way, like a harness, under and over the cat’s body. Its meandering breaks the trance and leads the eye around the form, over the shoulders, round the back. A tail of flexible conduit ends as a dotted ball akin to a microphone, emerging from a bolt at a control panel at the rear. The panel, the conduit and the aforementioned piping seem more than harness, more than ornamentation. They are part of the cat itself, a machine. On one side of the jaguar, underlying and overlapping the mechanization, South American flora and fauna camouflage the feline. On the other side, exposed in the gap between the jaguar’s fore and aft limbs, an airplane waits at a gate, maybe loaded, ready to push back. The vacant panes of glass, like eyes wrapping the cockpit, betray nothing about its cargo. The deserted airfield is likewise silent. Jason Walker’s illustrative ceramic constructions show wilderness and civilization, nature and culture, as they are—in dialogue. Simultaneously living and inert, vital and static, the central figure captures our attention. The illustrations draw us into the conversation.

It may be tempting to see the Southern Utah University professor’s juxtapositions and commingled industrial flora as a lament over the ostensible division between civilization and wilderness, but that would be a mistake. Walker’s work does not moralize. It does not bemoan humanity’s separation from nature. Instead, his boundary constructions present nature and technology interacting. They accept humans and their activities as part of the natural world. Walker pushes against the notion that humans and nature are separate and cannot meet. “We are not separate, because all these processes are on the planet, “natural,” in that sense.”

- Jason Walker, “Trophic Cascade,” on exhibit at NCECA’s 2025 conference in Salt Lake City.

- Detail from Trophic Cascade

- Detail from Trophic Cascade

Because Walker’s work incorporates nature and technology, many writers during the 2010s interpreted him as an “eco artist.” “Once you start combining ideas of technology and nature, people read that as sort of a push-pull between humans and the natural world in a way,” Walker says. “They say that that’s what it’s all about.” This was a time when Walker was receiving increasing recognition for his work, including NCECA’s International Residency Fellowship, which allowed him to travel to China and Hungary to make work before accepting a position at Emily Carr University in Canada (2012-2016). Although he creates pieces that embrace that dichotomy, and he considers himself ecologically minded and occasionally even political, he recognizes he is in no position to moralize. Even the simple act of making the sculptures requires resource extraction, after all. “Oof, mining, right? There’s no escape.” Ultimately, Walker makes work to understand things as they are. He leaves his own ambiguity visible and opens a door for us to enter his contemplation.

Walker contends that a work of art should tell something about the person who made it. For him, expression begins with the things he likes: the outdoors, animals, clay, cycling, industrial design, for instance. He then marshals them in relation to his direct experiences.

At first he only took imagery from his quotidian life but later sought out new experiences to gather imagery and feed his imagination. He tells his students, “as an artist, you sort of build what I call a visual vocabulary, especially when you’re working with representational imagery.” In his lexicon, birds and flying things relate to spirituality, fish signify material wealth, civilization-shy bears indicate wildness, and deer, coyote and foxes, which live on cities’ margins, denote civilization. The fecundity of rabbits reminds him of humanity’s teeming population. Industrial, mechanical and technological elements derive from machines he uses and facilitate a sculpture’s physical and metaphorical connections. Though intentional, Walker implies no hierarchy in the relative scale between the central animal forms and the flat, diminutive vignettes of civilization painted on their bodies. He has the tiny humans depicted in Hudson River School landscape paintings in mind, but every element works together to express his idea. He assures his student that no image or its associations need to be fixed—“after a while of using these images, you can kind of mix and match and play with them and juxtapose this with that, and see what happens,” he tells them.

Painting is an important aspect of Walker’s work and in his studio and around his house you’ll find several examples of his stand-alone paintings.

While in high school in the ’90s, Walker’s reputation as the kid who liked to draw landed him a job painting snipes on billboards in his home town, Pocatello, Idaho. On the billboard catwalk, amongst steel I-beams and bolts, spotlights and cables, he earned his facility with a brush and familiarity with industrial fixtures. While the billboards offered a sorry substitute for a tree, their situation in the landscape allowed him to work outdoors, his favorite place to be. After graduation, folks encouraged Walker to head to the arts program at Utah State, to become a graphic designer or illustrator. After a couple of quarters he retreated to Idaho State to complete his general education requirements, take a few ceramic and drawing classes, and save money. When he returned to Logan, his interest in illustration had waned. He felt a Luddite-like aversion to the increasingly computer-based field of graphic design and considers this his first moment of ambivalence toward technology. He intended to major in drawing and ceramics but the depth and scope of John Neely’s ceramics program surprised and inspired him and fused his bringing his painterly talents with clay.

“(John Neely) brought in this video of Alan Caiger-Smith, who painted lusters on his pieces with his big brush marks. And I was like, wow, I can do that, I can use a brush like that.” Neely was intrigued, so Walker explained how painting billboards rewarded speed and precision. Neely responded, “Really?” and the next day, as was his way, delivered a deluge of resources. Transferring his brush skills from a plane to a dimensional object amplified the artists enjoyment of painting. “Brush control was one thing on a flat plane. It’s a whole other thing, when you’re going around and you’ve got to turn (the surface) too. It was a blast.” Once he melded drawing with ceramics, Walker settled on ceramics as his major and graduated from Utah State with a BFA in 1996.

As an undergraduate, Walker benefitted from Neely’s emphasis on craftsmanship, but never had to confront or explore underlying ideas and motivations of the work he was making. When he entered graduate school at Penn State, every aspect of his making came under intense scrutiny and required introspection. He struggled to answer his instructors’ and colleagues’ questions about his concepts and choice of materials. Walker made a connection with a painting instructor named Paul Chester. When Chester asked him about the origin of the imagery he was employing and Walker replied that he “wanted, you know, to be influenced by nature,” Chester challenged him. “What do you mean by that word? What does it mean, nature?” In response, the artist started taking backpacking trips into cityscapes and into wilderness. He chose locales that complicated stereotypical notions of “nature.” When he left Penn State with an MFA in 1999 he had only a vague idea of the work he wanted to pursue. “Some people come out of grad school and then that’s the work they make and they make that forever, right? Not me. I just kind of barely tapped into it.”

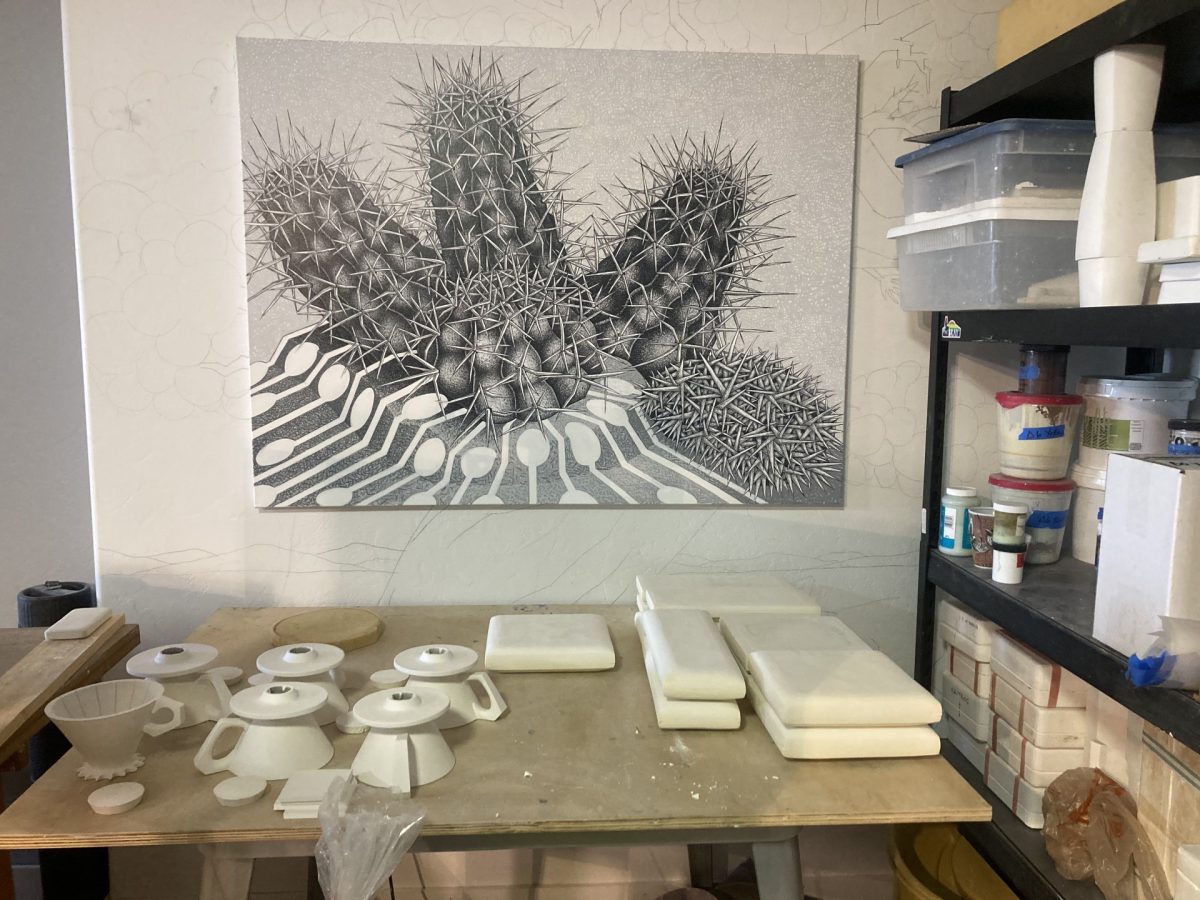

Walker carried his questions to Napa Valley Community College, where he worked as a lab technician and a ceramics and drawing instructor between 1999-2000. Between 2001-2002, under the auspices of the Taunt Fellowship, Walker entered a long term residency at the Archie Bray Center for the Ceramic Arts in Helena, Montana. During his tenure, he began experimenting in earnest with molds and slipcasting. He moved from casting molds of junkyard objects to combining these objects with clay, eventually making entire solid forms. Casting allowed Walker to componentize his visual vocabulary. Now, some of his pieces are completely slipcast from carved animal forms with parts that can be placed in myriad configurations.

Today, Walker works out of a home studio in Cedar City, not far from Southern Utah University, where he has been teaching since 2019. Although he continues to work primarily in clay, he doesn’t consider himself a ceramic artist, but an artist who works with ceramics. He particularly likes clay for its dimensionality and mutability, qualities that allow him to manipulate perception and blur the boundary between nature and technology. “If I used a metal bike chain, you’d go up to it, you’d touch it, and think, oh, it’s just a bike chain. But if you go up and you’re like, oh, it’s ceramic, you’re going to think about it, you’re going to perceive differently now, this new thing in a different material.”

- Mechanized Life: The Jackrabbit (2007), porcelain and underglaze, 15 x 13 x 12 inches

- Seagull in the Desert (2007), porcelain, underglaze, and earthenware, 15 x 12 x 10 inches

While at Napa Valley Community College, Walker lived kitty corner from the library. Through its catalog, he became a student of Roderick Nash, Neil Postman, and Marshall McLuhan. Nash’s Wilderness and the American Mind clarified the cultural metamorphosis of wilderness in the United States. Postman’s Amusing Ourselves to Death and Technopoli informed his views on technology’s effects on the human psyche. McLuhan’s “The Medium is the Message” confirmed his nascent ideas about technology’s effect on perception. These authors have continued to influence Walker’s output. For example, “Manifest Destiny” (2007) emerged from Roderick Nash’s telling of the view of wilderness during the mid 19th century, when the nation framed nature as a fearful place to be tamed. But by the time John Muir made his fight for Yosemite Park, humans saw wilderness as a retreat from their mechanized lives. Walker’s “Seagull in the Desert” (2007) and “The Jack Rabbit” are part of a series of mechanized animals exploring his understanding of the world in these terms. These writers and their ideas continue to inform his work.

While his work does not impose a hierarchy between nature and technology it does acknowledge technology’s alteration to our understanding of our relationship to nature. Walker draws a McLuhan-like scenario to illustrate the point: eyesight was a matter of survival before eyeglasses but their intercession gave the vision-impaired a leg up on nature, leading some to conclude that this technology lifted them above natural laws. Alterations to perception are inherent in every tool we employ, Walker says. “Whether it be a pencil, whether glasses, or a computer. All these things have underlying messages and unknown consequences that change our social structures and our perceptions of the natural world.” When unconsciously adopted, each new technology widens the gap between humanity and nature because its promised effects gives us the illusion of control. This effect may underlie the supposed separation of the human world from the “natural” one.

Walker sees humanity’s yen to control nature and nature’s pushback as interplay, not conflict. In his view, all tools have benefits and consequences. The danger occurs when we adopt technology and use it unquestioningly, a dynamic he explored in his 2012 Blind Admiration Series. Ultimately, the division between humanity and nature cannot hold because even the fanciest technology cannot overcome embodiment. “Our corporeal experience, the fact that we have bodies, that we live and die, is the one thing that links us to nature that will never be able to change,” says Walker. Since that series, Walker has been playing with the bodily experience and the unalterable constant that embodiment means mortality and death subjects all humans to nature.

Walker recalls a recent experience while riding his bike on a mountain trail in Oregon. When he came around a corner, a high bush blocked his view of the next bend. He thought he saw a raccoon bolt across the trial but as he approached the curve he startled something else—a creature jumped over the bush in front of him, then turned and looked at him. “Holy shit, that’s a mountain lion” he thought and skidded to a stop. He watched the lion bound down the hill and hollered at it to keep on going. With nothing to defend himself and no desire to be food, he abandoned his ride. “It’s really interesting,” he reflects. “I don’t think we feel that anymore. Nobody feels that vulnerability of, like, I could have just been eaten.” His recent work, exhibited at Ferrin Contemporary in North Adams, Massachusetts, confronts his, and our, corporeality head on.

The artist’s interest in embodiment arises from his observation of our increasingly tech-mediated experience. The effects are so pronounced that some human beings barely put their bodies to use. Despite these trends, Walker remains unopposed to technology. He simply hopes we can become intentional in our use of it. “Now I see (the relationship) as sort of symbiotic, complementary.” Civilization gives us the means to appreciate and understand Nature. Nature, especially when we are out, unprotected in the elements gives us the means to appreciate the advantages of civilization.

Clay Arts Utah presents a Masterclass with Jason Walker at Sunstone Ceramic Studio, October 25 & 26.

Walker’s work is on exhibit at SUU Faculty Exhibit at the Southern Utah Museum of Art, Cedar City through March 7, 2026.

Brandi Chase is poet, student, teacher and maker of pots (most often, but one never knows). She loves red lipstick.

Categories: Artist Profiles | Featured | Visual Arts