John Neely in his studio. Photo provided by the artist to the author in 2024 as part of promotional materials for Clay Arts Utah workshop.

Nationally and internationally renowned researcher, potter, and beloved educator John Childs Neely IV passed away at his home in Logan, Utah on Sunday, June 1. He was 71.

His colleague, Massachusetts-based studio ceramicist Christopher Gustin, described Neely as “an ambassador who traveled the world passing on his knowledge and love of the handmade object, and his deep respect for those who brought beauty into this world through the act of making things with their hands.” (Instagram post, June 3, 2025).

Neely made a significant impact on the ceramic arts and shaped other artists’ approach to the medium. His work has been presented in more than 100 group and solo exhibitions in the U.S., Europe, and around the Pacific Rim. It is held in permanent collections across five continents and held (and most certainly handled) by private collectors the world over.

Neely committed himself to the study of the art and science of ceramic technology and shared his findings internationally through lectures, workshops, and publications including Ceramics Technical, Ceramics Monthly, NCECA Journal, Purple Sands Magazine, Studio Potter, and Ceramics: Art and Perception. He is most known for his development of the wood-fired Train Kiln and reduction-cool firing method, which he described as a way to achieve aesthetics analogous to that of traditional Japanese Anagama kilns while using less space, time, and fuel.

Since 1984, Neely has held the position of Professor of Art in Ceramics at Utah State University in Logan, UT. He fledged and nurtured the prestigious ceramics program there and prepared generations of potters who have gone on to become influential ceramicists in their own right.

In 2013, Neely became the first Fine Arts faculty member at USU to receive the prestigious D. Wynne Thorne Career Research Award. He was inducted as an Honorary Member of the National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts (NCECA) for his outstanding contributions to the field in March 2025.

Education & Influences

Born in 1953, John grew up in Leavenworth, Kansas. He found clay in high school at 15 and deepened his love for the material with two years at Wichita State College of Fine Arts under the guidance of Rick St. John. St. John emphasized quality and craftsmanship, both hallmarks of Neely’s work. In his sophomore year, Neely developed an interest in German salt-firing technology but decided to study Japanese (and did so with gusto!) instead of German because the latter treated ceramics as a trade rather than a university subject.

While intensifying his study of Japanese under the Stanford Language Program, he learned about Colorado University’s year-long Kyoto Seminar in Art and Religion. In 1973 and 1974, as part of this seminar, he lived in a homestay and worked at the Buddhist Otani University in Kyoto. During the seminar John brought “the arts’ view” to bear on a wide range of topics within contemporary Japanese culture. The experience grounded him in Japanese issues of the day, and sparked his affinity for the country and its ways.

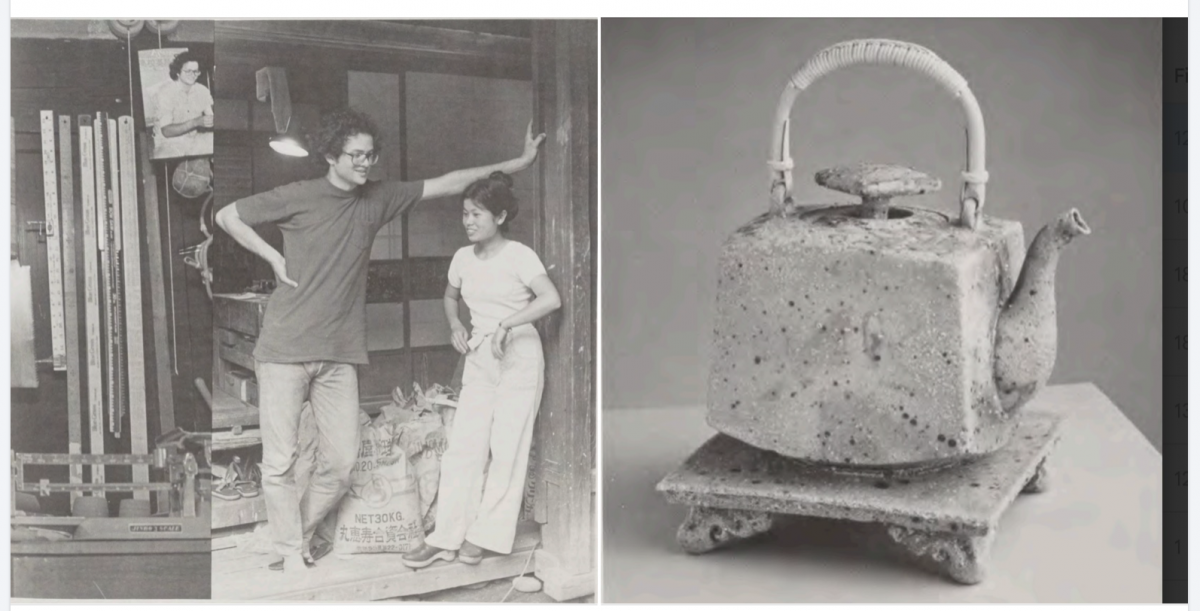

John Neely and Atsuko Ohno standing together at the traditional wooden home in Japan Neely restored.

Neely finished his BFA at the New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University in 1975 and was awarded a Rockefeller Brothers Fund Fellowship. Through this fellowship, he attended the Inter-University Center for Japanese Language Study in Tokyo. While there teaching at an English language camp the summer prior he had met Atsuko Ohno, his bride-to-be. They married in 1980.

In 1983, after finishing his MFA with Ceramics emphasis at Ohio University School of Art and Design under Joe Zeller, Neely returned to Japan as a research fellow at Kyoto City University of Arts. His longing to remain in the country compelled him to create a studio from the ancestral home of Atsuko’s father in Kisarazu, Chiba. The house, worse for wear and slightly off-kilter, became another vehicle that would deepen his appreciation of Japan. He repaired the thatched roof, re-papered the screens, reclaimed its wood to form pottery-making tools, and learned a great deal about Japanese construction methods.

So it was, over a span of 13 years, all while attaining a BFA and MFA, Neely spent 10 of them living in Japan. He traveled widely during his sojourn there and shared many meals with significant people in contemporary Japanese art. Their customs around eating and drinking influenced his understanding of the culture and deeply informed the things he valued in the world. The relationships and values he built during that time continued throughout his life.

“John’s journey to Japan in the 1970s to study its distinguished, unique cultures and traditions led to lasting friendships with many Japanese potters,” wrote ceramicists Hitomi Shibata and Takuro Shibata (formerly of Shigaraki Japan, now directing Starworks Ceramics in North Carolina), shortly after his death (Instagram, June 6). “He built significant cultural bridges between Japan and the United States. His fluency in Japanese, coupled with his profound historical and technical understanding of Japanese pottery, demonstrated his respect and commitment to our culture. A true legend, John’s extraordinary contributions to ceramic arts, his commitment to cultural exchange, and his unwavering support for the pottery community connected potters worldwide.”

While still living in Japan, Neely applied for a job in Logan, Utah as professor of art in ceramics at Utah State University (USU). Despite being interviewed and hired over the phone, he felt optimistic about its prospects because Larry Elsner, the man in charge of the search committee, was also married to a Japanese woman. During the in-person interview, the landscape surrounding USU’s campus quashed any remaining doubts—Neely imagined himself fishing all summer and skiing all winter. But little fishing and skiing was to be had. It was 1984. Atsuko and John welcomed their only child, Erika, in February of that year. Neely set to work building what would become a venerated ceramics program and establishing his reputation as a prodigious researcher, an artist and craftsman, and a revered educator.

Train kiln built by Neely student Ted Neal at Midwestern State University. The kiln is a variation based on Neely’s original concept and Neal’s extensive, iterative experience. The build took place May 27 – June 3, 2025. Photo by Jaylei Lamb.

Researcher

While the technical information Neely developed and disseminated over his career was broad and immense, the development of the Train Kiln and the “reduction cooling” approach to firing has shaped the aesthetics of wood-fired ceramics and made Utah State a world-class wood-fire research institution.

Neely’s interest in firing technology was with him from the start, particularly the effects of atmospheric conditions within the kiln on color production in clay. While in Japan, he centered his investigations on the possibilities during the firing process. Two existing kiln designs informed his inquiries: the Push-Me-Pull-You and the traditional Anagama. Though differing in size and firing techniques, in both kilns fire and ash rise through the wares. John found the long, uphill climbing Anagama kiln cumbersome to load. Moreover, it required several days and mountains of wood to reach temperature. By contrast, the upright and compact Push-Me-Pull-You kiln quickly and efficiently achieved temperature; but it required the potter to lay on the ground to feed the flame—untenable for an exceptionally tall potter like Neely.

An internal grant from USU enabled Neely to build the first iteration of his “train kiln.” Despite the obvious need, he did not set out to address efficiency and ease of firing. His decision to relocate the firebox above rather than below the ware chamber came from a desire to control the draft’s movement and improve the distribution of fly ash onto the pots and ultimately their color. This relocation allowed potters control over airflow, ensured complete combustion of the fuel, and was replicable at most any scale. It also gave the kiln its distinctive locomotive shape.

As Neely fired this kiln, he noted that an excess of oxygen during firing left the iron in the clay body red, whereas with insufficient oxygen (a “reduction atmosphere”) the flame extracted an oxygen molecule from the iron (FeO₂) and turned it black (FeO). He postulated: if a pot were pulled from the kiln at that state, it would be black, but as the oxygen rich air cooled it, it would re-oxidize to a brown. Recalling an article about excavated cast-iron black pottery in Korea and the unusual presence of unburnt fuel in the kilns there, he theorized and later proved that the fuel had been smothered intentionally to maintain a reduced atmosphere while cooling to produce black pots. Neely called his scientific understanding of this ancient method “reduction cooling.” He continued to explore color variations and atmospheric conditions with his colleagues Dan Murphy at Utah State, Hideo Mabuchi at Stanford, and Ted Adler at Wichita State University.

When Utah State University awarded Neely the D. Wynne Thorne Career Research Award in 2013, Chris Terry, Associate Dean of the Caine College of the Arts, said of Neely’s findings, “In order to understand how impressive this achievement is, one only has to consider that mankind has been experimenting with firing clay ever since people began to experiment with fire. Thus, it would be safe to assume that it would be nearly impossible to come up with an innovative way to fire clay, but John Neely accomplished just that.”

Artist

Neely referred to himself as “the Myopic Potter.” Utah State alumni Ernest Gentry described the moniker as Neely’s humorous, self-acknowledged awareness of his nearsighted perspective and tendency to focus on minutiae, yet with a willingness to leave the outcome to happy chance. On the occasion of a joint exhibition with Dan Murphy at The Island Gallery, Bainbridge Island, Washington in 2012, Neely said,

“There’s a funny mix between control and discovery. You know there is a certain measure of control or a certain attempt to control. There’s also, you know, a certain amount of serendipity. It’s like fishing, you know? If you don’t bait the hook and throw it in you aren’t going to get anything. So chance favors the prepared mind or something like that. It’s finding a balance between those things. It’s part of the pleasure of it, of course, the discovery part of it to do things that you didn’t plan.”

Although Neely specialized in utilitarian tableware, primarily drinking and pouring vessels, he never limited his interest in ceramics to the kinds of objects he made. He saw utility on a continuum with the general idea of containment on one end and a specific single purpose tool on the other. In this view, the teapot becomes a “machine” for brewing and serving tea, but also a means to explore the materials and processes necessary to achieve a specific form.

Neely leads a workshop for Clay Arts Utah held at Iron Desert Arts, September 28-29, 2024. Photo by Antra Sinha.

Educator

Neely’s research lay, of course, in how to use art and technology to his own ends, but also, and perhaps more impactfully, in helping his students and others use them to their ends. Because ceramic practices integrate geology, chemistry, physics, material science, and combustion engineering with design, art history and material culture, Neely felt strongly about its aptness for the university setting. Although his artwork revolved around tableware, his fascination with ceramics and the knowledge he could impart encompassed the entire breadth of the discipline.

Neely wore the diverse artistic outcomes of Utah State alums as a badge of honor. He said of his students, affectionately, “They are all over the map, both literally, I mean they’re spread out all over the world, but they also range from potters to sculptors and everything in between.”

Neely’s experiences living in Japan honed his appreciation for the way Japanese rituals concerning food and its display shape its culture. His respect explains, in part, his focus on vessels crafted for the table, but also the underlying generosity and mindful attentiveness to the needs of his students. He and Atsuko often hosted students and visiting artists for meals and discourse at their home. John often declared that more education went on around his dinner table than in the classroom. In an Instagram post on June 6, USU alum Hamish Jackson remembered these meals with the Neely’s and his cohort as the highlight of his graduate experience: “We learnt much in these moments, using the pots and chatting about them…To be able to do this with your mentor and such fabulous pots was a gift. I hope to facilitate learning in this way as I carry on in the clay community.”

On the same platfrom, NCECA Board President Shoji Satake wrote of Neely’s legacy: “(It) isn’t just in the kilns he’s built or the artwork he’s made. It’s in the people he’s impacted along the way. His students and anyone lucky enough to have spent time with him carry his lessons with them. Our community is stronger, more connected, because of his generosity, his dedication, and his belief in sharing what he knows.”

Farewell

Neely is survived by his wife Atsuko and daughter Erika, and her partner Dorian; his mother, LuAnne; brother-in-law, Satoshi Ohno; and many beloved friends and extended family. His father, John Childs Neely III; his sister, Terril Anne Neely; and his in-laws, Akira and Tomi Ohno, preceded him in death.

Neely loved classical music and jazz, particularly the gypsy jazz of Django Reinhardt and the like. He played guitar in that style as part of a Logan-based jazz ensemble.

A memorial will be held on September 13, 2025, at Utah State University’s Russell/Wanlass Performance Hall. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the John Neely Ceramics Scholarship Endowment at https://usu.edu/johnneely.

Ceramics Arts Network has made a video of a recent conversation between John Neely, Pete Pinnell and Simon Levin free through June.

John Neely walking back to the classroom from the kiln yard at Utah State University. Image by Paige Harper.

.

Categories: In Memoriam | Visual Arts