Memories and dreams, ceremonies and dancing, family and community—all are reflected in the BYU Museum of Art’s Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu (Past and Present Together), where stories are told in meandering pathways of paint and pattern. Curated from the collection of the Kluge-Ruhe Aboriginal Art Collection of the University of Virginia as well as a handful of private collections (including actor Steve Martin and his wife Anne Stringfield), the exhibition explores the history and impact of Papunya Tula Artists, Australia’s first Aboriginal-owned art company established in 1972. For more than 50 years, these artists have told the stories of their ancestors simultaneous to sharing the lives and dreams of their contemporary communities in Australia’s vast desert.

The exhibition is expansive and beautifully laid out in the lower galleries of the Museum. The wall colors provide a balanced, color complementary backdrop to the shimmering reds, oranges, and yellows of the paintings. In fact, they enhance the vibrations emanating from the works while reflecting the deep blue sky and sandy brown of the desert environment. The generosity of the gallery space allows room for full viewing of these mostly large paintings (though you really should get up close to see the details as well). Didactic and extended labels guide visitors through the stories of the art company, the artists, and the contextual themes found in the paintings.

A gallery view of the Papunya Tula Fiftieth Anniversary Suite, with 50 square canvases arranged in a grid along the far wall. Each canvas features a distinct pattern or design, forming a colorful mosaic of Aboriginal contemporary art.

A few highlighted works welcome you into the exhibition in the foyer space, punctuated on the left by a huge, curving wall featuring the Papunya Tula Fiftieth Anniversary Suite. To celebrate this anniversary, the Kluge-Ruhe Museum invited the artists to curate works by 50 top artists. The result is a mosaic of pattern, form, and color that encompasses all that is to be seen in the main gallery beyond.

Not bound by strict chronological order, the exhibition does successfully establish the early works of founding artists just inside the main exhibition space. The earliest members of the group used the materials at hand, which included discarded building materials, fruit crates, cardboard, and linoleum tiles. These base materials are not immediately evident behind the cacophony of paint, but they do reflect the artists’ situation. Papunya was a government settlement formed in 1971, bringing together people from different language groups from all across the desert, into cramped and unfamiliar new living conditions. Much like Indigenous people in our country, the artists of Papunya used newfound materials to help them hold onto their ancient cultural traditions and connections to their homelands.

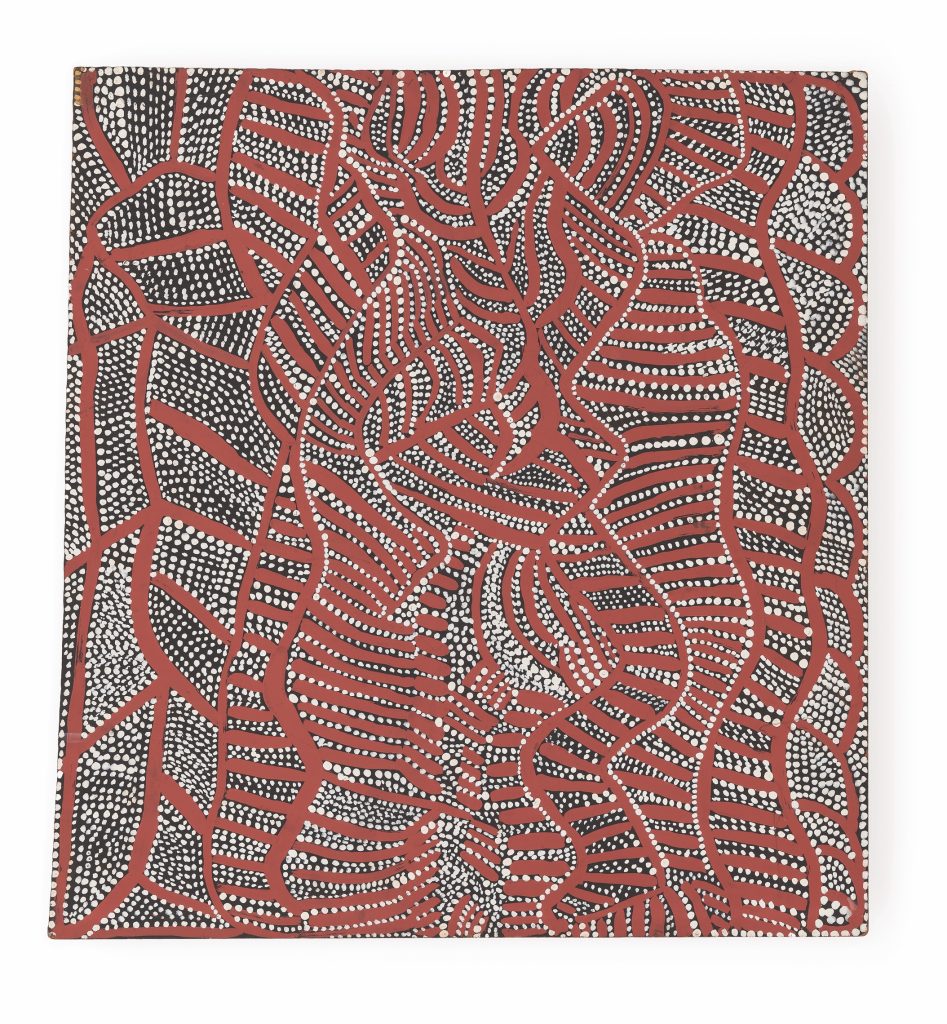

In pieces like John Kiparra Tjakamarra’s “Tingarri at Kulkurta,” from 1972, and Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula’s “Yala Tjukurrpa (Desert Yam Dreaming),” from 1971, the strength of the art consortium’s style is apparent from the very beginning. Bold lines and expressive dots create a visual story that is surprisingly clear and to the point. Immediately abstract, these two paintings vibrate with life and power that activates the eye and sparks curiosity.

And the same can be said for nearly every other piece in the exhibit. This consistency of the style, though, is—surprisingly—not repetitive in effect. Every piece seems to have its own voice and tale.

Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula, “Yala Tjukurrpa (Desert Yam Dreaming),” 1972, synthetic polymer paint on composition board,

20 × 181/2 in.

Though Papunya Tula Artists was a predominantly male group, women found a place early in the company’s formation as well. Many of these women artists, like Makinti Napanangka, brought a more gestural style. Her triptych “Lupulnga,” from 2005—2006, depicts a rhythmic dance skirt called a nyimparra. The contrasting direction of pattern emphasizes the active lines that reflect the energy of the dancers. “Lupulnga” hangs with seven other works by women artists and, as a group, they start to feel like the sounds of different musical instruments playing together, all against the complementary deep blue wall that implies the magnitude of the sky when you stand (or dance) in the middle of a desert. It’s an invigoratingly palpable energy.

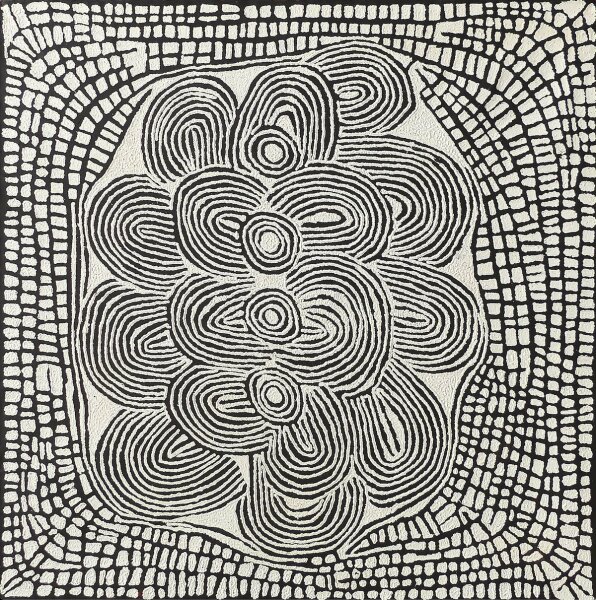

Ningura Napurrula’s “Wirrulnga,” from 2001, has a different kind of energy. Wirrulnga is a birthing place, where women came for centuries to give birth to their children in community with other women. In the painting, the forms are gathered as if petals on a flower, supporting each other, and supporting the central line of circles that seem to reference the new babies. The scale of the piece adds to its impact, as does the simple black and white palette. The rock-like border harkens to the safety of the site, protecting the women and babies at their most vulnerable moments.

Ningura Napurrula, “Wirrulnga,” 2001

Though the consortium of artists is a business, much of the money they’ve raised over the years has gone back into their communities. In 2000, artist Patrick Tjungurrayi led the group in creating a collaborative canvas to auction and raise funds to build Purple House health clinic. In 2009, Patrick was diagnosed with kidney failure and once again led a fundraising effort to establish a dialysis center in the community. Without that, people had to travel 1,600 miles to Perth to receive these services. It is not uncommon for artists to be on the ground floor of community development, though their contributions are often overlooked. The linear patterns in Patrick’s piece “Mayililinnga,” from 2002, seem to form a tight-knit village reflective of this emphasis on community.

The community and environment of the Papunya Tula artists is explored in an adjacent interactive gallery that includes video interviews, maps, large-scale photo murals, and a reading nook that expands on the stories told in the exhibition. It also brings the voices and language of the Aboriginal artists to life. A long-standing tradition in art museums, this type of educational gallery is particularly critical to sharing the heritage, culture, and context of Indigenous artists.

Irrititja Kuwarri Tjungu is a large exhibition that covers over 50 years of work by dozens of artists. At first look, there is a homogeneous style that gives it the feeling of an exhibition from 20-30 years ago (accentuated by the classic museum architecture of the BYU Museum) but getting up close to the paintings leaves you with an unexpected vibrancy. Though we may not be familiar with the ceremonies or cultural history, the paintings still sing and dance with life.

At the BYU Museum of Art, cozy reading nook features Indigenous-themed children’s books, circular floor cushions, and a chair. The adjacent wall displays a grid of portraits of Aboriginal artists and a screen playing video interviews, highlighting the personal and cultural connections behind the art.

Irriṯitja Kuwarri Tjungu | Past and Present Together, BYU Museum of Art, Provo, through December 6.

Gina Cavallo has been a curator, registrar, and executive director in museums for over 35 years. She spent many years as an art critic for publications in Phoenix. She began her career at the Phoenix Art Museum and the Heard Museum, was a founding curator at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, spent two terms managing exhibitions at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and was the Executive Director at the Mission Inn Foundation & Museum in Riverside, California. Her current role is Director of Development for Taproot Theatre Company in Seattle where she also serves as the curator of the Kendall Center Exhibition Series. She moved to Orem in 2024 with her husband, a theatre faculty member at UVU.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts

For a view of the art, take a look at

https://artistsofutah.org/15Bytes/index.php/abstraction-and-the-dreaming-at-the-nora-eccles-harrison-museum-of-art/