Installation view of Underground Library at Finch Lane Gallery, with Andrew Rice’s small-scale collages displayed alongside Jason Manley’s text-based sculptural walls.

Unexpectedly situated in the westernmost gallery space at Finch Lane, Underground Library presents the paired works of Andrew Rice and Jason Manley. The exhibition’s title evokes secrecy, buried knowledge, and invisible systems of thought, and the two artists deliver dramatically different yet eerily complementary contributions to this theme.

Rice and Manley’s practices diverge in scale and sensibility. Rice offers small, precise collages built from comic book imagery—intimate, restrained, and loaded with pop-cultural resonance. In contrast, Manley’s ArchiScript series, composed of CNC-milled wooden text embedded into large-scale wall-like structures, forms a metaphorical architecture. The contrast between micro and macro, private and public, is immediate and striking.

Yet despite their differences, both artists traffic in fragments—scraps of memory, cultural detritus, and personal symbolism. Their installations explore the unstable ground between memory and reality, critique and hope, the individual and the collective.

ason Manley’s ArchiScript series fills the Finch Lane Gallery space, the carved wooden text walls casting intricate shadows across the floor.

Manley’s sculptural walls physically divide the gallery, acting as both structure and story. His script—an amalgamation of journal entries, fiction, poetry, and hypothetical screenplays—resists linear reading. The form recalls the cut-up techniques of William S. Burroughs and the intermedia poetics of Fluxus. His words aren’t simply written; they are built, embedded language made architectural.

Drawing on the ideas of Robert Smithson, Manley constructs a lattice of memory and metaphor. These wooden structures, titled “ArchiScript: Corner, Closet, and Screenplay,” recall the dimensions of the artist’s old home. They are literal walls, but porous ones, full of gaps, erasures, and visual footnotes. Arrows and bracketed broken notes suggest intention, but the narrative never resolves. It loops, fragments and recedes.

The result is less a house than a subconscious map of one, a site where fig trees, fog-wrapped carnivals, window galaxies and broken syntax mingle freely. The writing is immersive, like a lucid dream with no anchor in time. One phrase stands out: “He lives entirely within his imagination.” This could describe the work itself or the viewer within it. Imagination here is not escape, but existence.

Detail of Jason Manley’s ArchiScript installation at Finch Lane Gallery.

The installation confronts us with a paradox: it is stable in form, yet unstable in meaning. It evokes entropy, the gradual breakdown of narrative coherence, and resists neat closure. “Not a Hollywood ending,” the script reminds us. The Ferris wheel of memory turns, but never arrives.

As viewers pass through the corridors between Manley’s sculptural walls, they move through a temporal collapse, past and future folding into a single sensory experience. The “home” referenced is not static. It grows like broccoli, mutates into mazes and infinite floors. It is biological as much as architectural, lived through more than lived in.

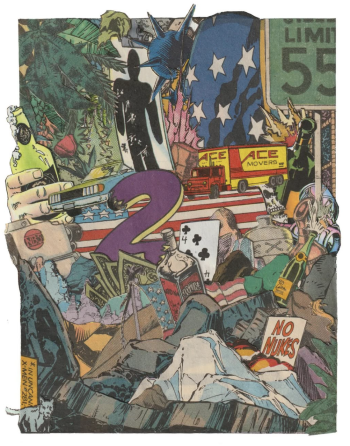

Andrew Rice, “NO NUKES,” collage on board, 4.5 x 6 in. .

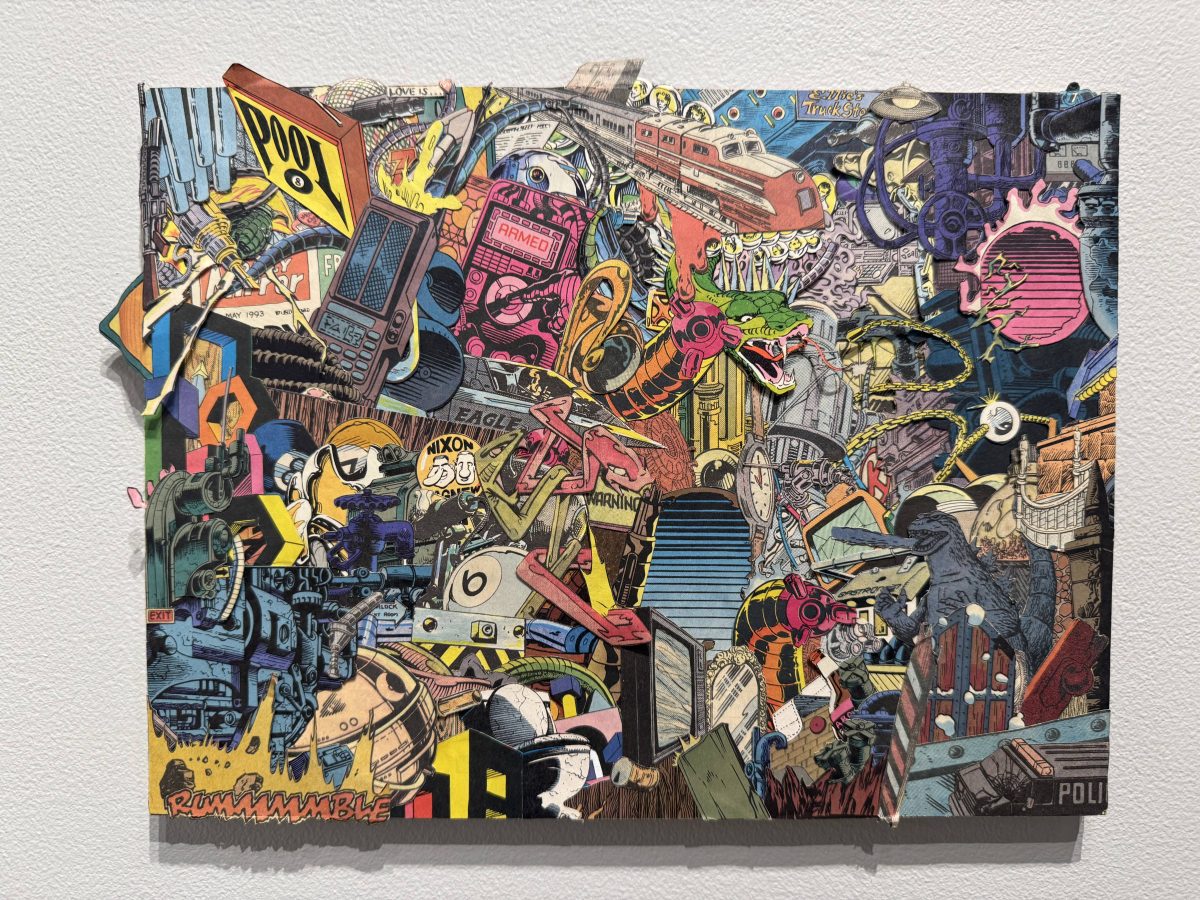

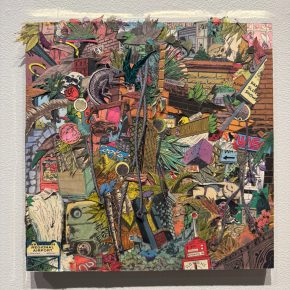

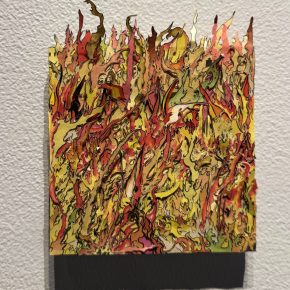

While Manley builds memory into space, Andrew Rice condenses cultural anxiety into collage. Titles like “No Nukes,” “Let It Burn,” “Trauma,” “Say Less,” and “Here We Are Again,” and “Police State,” set the tone a kind of satirical pessimism, equal parts cultural critique and personal reckoning. Each work is meticulously assembled from cut comic book fragments and vintage ephemera. All these images of flags, fire, figures, weapons, and everyday domestic objects are curated with symbolic intent.

“No Nukes” presents bottle silhouettes, comic style bomb bursts, scraps of flags, and shadowy figures, all layered beneath its stark title. What’s striking is not just the content, but the curation: each fragment is loaded, chosen to resonate across decades. Though rooted in mid-century design language, the work speaks urgently to the present.

Rice’s compositions often mourn a future that never arrived. They reflect on the techno-optimism of the ’80s and early 2000s, a time when progress felt dreamy and utopian. That dream is now rendered in decay, burned out in pieces like “Let It Burn II,” where flames engulf a rigid form in a recursive wash of stylized destruction. Fire, in Rice’s work, is not just danger but inevitability and a symbol of collapse disguised in the polish of pop media.

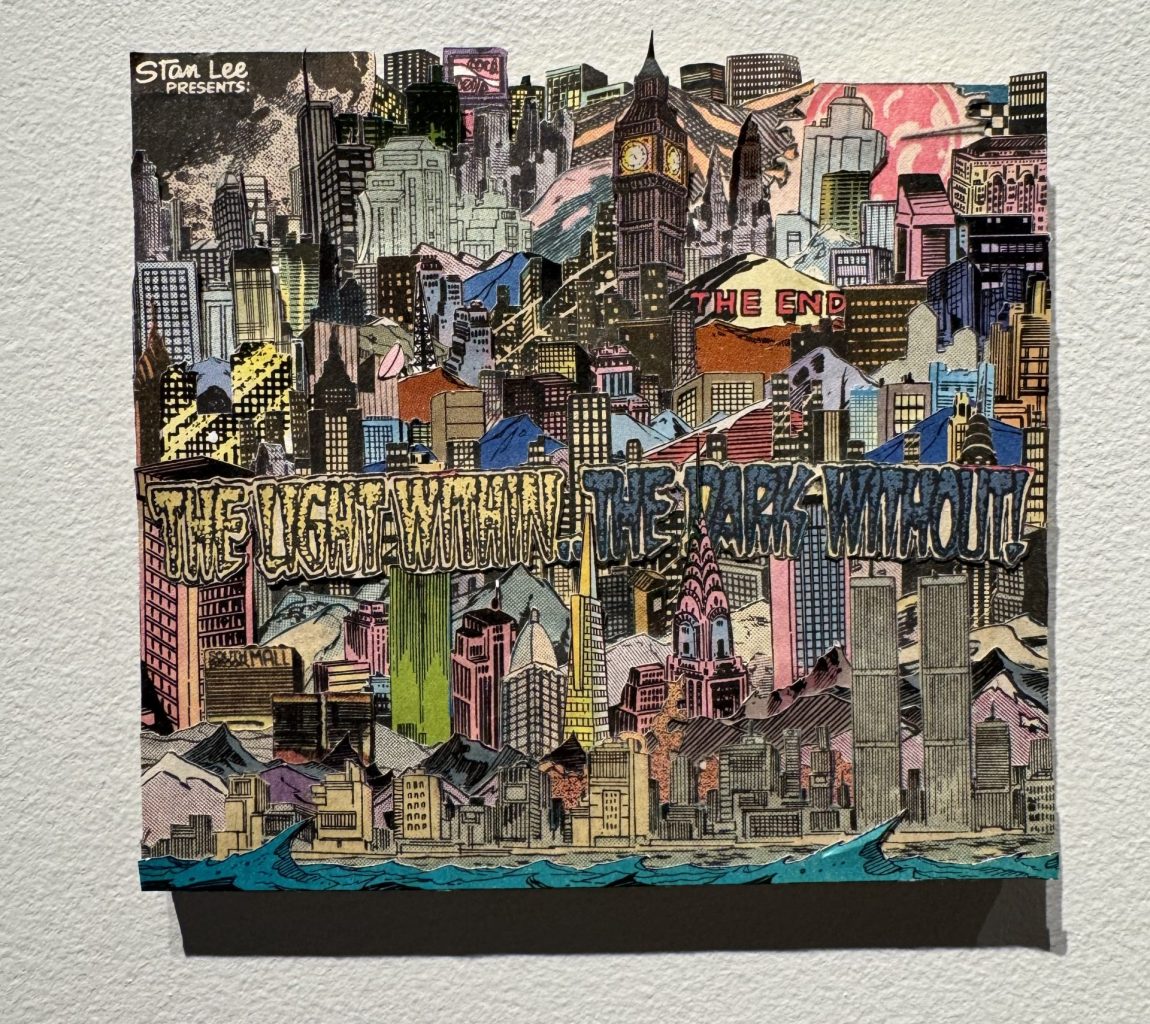

Other works, like “Trauma,” situate viewers in voyeuristic domestic interiors: tiled floors, radiators, Bibles, couches, chains. These spaces feel lived in, but fractured, as if memory has been disassembled and reassembled out of sync. In “The Light Within the Dark Without,” Rice continues this binary, balancing beauty and dread, order and chaos. His visual language borrows from collective memory, but recasts it as personal unrest.

Andrew Rice, “The Light Within, The Dark Without,” collage on board, 6×4 in.

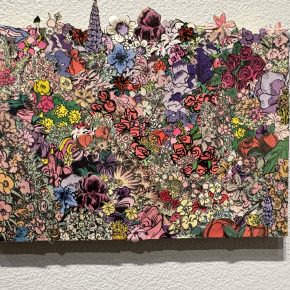

- Andrew Rice, “Bouquet,” 6×4 in.

- Andrew Rice, “Automatic On,” 10×10 in.

- Andrew Rice, “Let it Burn 2,” 4×4 in.

In “Automatic On,” the addition of gold leaf adds a material shimmer that reflects light, pulling the image into three dimensions. Some collage elements peel from the surface, breaking the frame and increasing the tactile immediacy. In “Sullivan County,” explosions and weather phenomena give the image cinematic urgency, while in “Bouquet,” Rice offers a rare moment of pause. Composed entirely of floral forms in varied hues and textures, the piece feels sincere, maybe even hopeful—a moment of care within a practice steeped in collapse.

Taken together, Manley and Rice offer an Underground Library, not of books, but of emotional documents and interior landscapes of cultural drift, imaginative survival, and memory under pressure. One builds text into walls; the other pulls images into fragments.

Andrew Rice, “Ellie’s Truck Stop,” collage on board, 12×9 in.

Underground Library, Finch Lane Gallery, Salt Lake City, through September 12.

All images courtesy of the author.

Raised in a creative Michigan household, Nolan Patrick Flynn developed an early passion for art. He moved to Utah to pursue an MFA at the University of Utah and continues to create art out of his Salt Lake City studio and teach high school art at Stansbury High School.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts

Here’s my hypothesis as to why this show was in the back and not the front. By so placing it, the artists and the gallerists were able to use Jason Manley’s ArchiScript like real architecture, which divides the gallery into two parts, each accessible only indirectly, through one of the room’s two symmetrically-placed doors. Whether you think of language as an impediment or a powerful tool, here its strength is experienced for real, in actual space, with measured tread, and on the scale of a human body.