The complexity and rich magnificence of Victorian art comes to the fore at the Brigham Young University Museum of Art’s exhibition of works from the collection of British entrepreneur Thomas Holloway. Amassed between 1881 and 1883 to decorate the women’s college Holloway founded in 1879, the collection consists of 77 masterworks of the era, 60 of which are on display at the Museum through October 24. Painted in the realistic manner in vogue at the time, these works appear like headlines from the newspapers of a bold, lavish era fascinated equally with progress and social reform as well as a romanticized vision of everyday life and English history.

The Victorian age was a vociferous epoch of politics, philosophies, aesthetics, morals and ideas that contributed to a century of intensity and progression. Due to the influence of poets like Byron and Shelly, and the ideas of the sublime in Edmund Burke, the Victorian age had strong ties to the Romantic era, but was also struggling with the realities of a quickly urbanized and industrialized modernity. A number of artistic tributaries, native and foreign, fed into the great river of creative output that created these works. The political realism of Daumier in France, or Dutch masters who painted genre scenes of everyday life or the Germans like Caspar David Friedrich who painted glories of the sublime, all find their way into these pieces.

Like a Dickens novel, a poem by Blake or an essay by Ruskin, the paintings in this exhibit tell stories, reveal Victorian pathos, explore romantic sensibility…they are a sampling of Victorian Painting (with the exception of the work of the Pre-Raphaelites and the general trend towards medievalism in Victorian art, which was amply displayed in an exhibit at the MOA last year).

Reflective of English sensibilities, one of the main themes that can be gleaned from this body of work is the attention the artists devoted to portraying social commentary. The Victorian political climate was one of change and reform. Though most of the works in the exhibit are from the late 19th century, the English interest in social reform goes back at least a century, as seen in George Moorland’s “The Press Gang” (1790). Over the century, interest in social reform continued: child labor laws were enforced, woman’s health issues and civil rights were furthered, the needs of the poor were tended to and the conditions of hospitals, orphanages and asylums were made a point of reform.

The social concerns that appeared in novels by Dickens, Elliot and Bronte are given visual flesh in works like “Applicants for Admission to a Casual Ward,” painted by Sir Samuel Luke Fildes in 1874. A monumental piece that is one of the first works the viewer encounters upon entering the gallery, this lush, densely-painted work depicts a concourse of those with “casualties.” We see the destitute, the sick, the hungry and homeless, but our focus is on the most sympathetic of Victorian images, the young mother with babe in arms, another child holding on to the hem of her dress. Fildes’ image is not merely a painting of the tragedies that were a part of the reality of everyday London, but is an encouragement for more awareness and a sympathetic attitude to these unfortunates. It is a theme that can be seen in many of the paintings and one that dominated English politics and society in the 19th century.

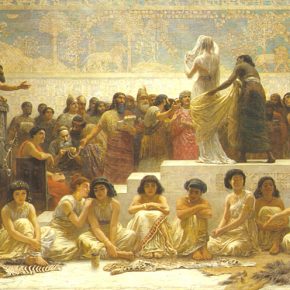

Acting almost as a balance to the everyday concerns of social reform and harsh realities of their modern life, the Victorians interest in historical and dramatic scenes is evident in many works, like “The Battle of Roveredo,” and “The Emperor Charles V at the Convent at Yuste.” This last, together with “Expulsion of the Gypsies from Spain” and “Licensing the Beggars in Spain” reveals an interest in the history of imperial Spain that may reflect Britain’s concern for its own swelling empire. Tito Conti’s “Good-bye” and John Pettie’s “A State Secret,” though set in historical milieus, are more dramatical than historical, and their continental (and Catholic) overtones were meant to satisfy the Victorian desire for exoticism that was fully satiated in works like “Relatives in Bond” and “The Babylonian Marriage Market.”

- The Emperor Charles V at the Convent at Yuste, by Alfred Elmore, 1856

- “A State Secret” by John Pettie

- “The Babylon Marriage Market” by E.L. Long, 1875

As these paintings reveal, regardless of the local or historical setting of the paintings, narrative was a dominant drive in Victorian art. A painting might show the crowded stations of the modern railroads in the large cities, or the drama of a lost fisherman on the rural coast, but they were all meant to give the viewer a narrative they could decipher.

This force came both from the tradition of historical painting that had dominated the academies of art, as well as the English tradition of genre scenes. This form of painting is a descendant of the Protestant necessity to avoid religious imagery of saints and Virgins, the strong emphasis on portraiture, narratives with the quality and substantiality of Hogarth, and Gainsborough, Reynolds, or Romney, leading to a tradition that would paint the aristocracy and pauper equally, with veneration for verisimilitude. This tradition of the genuine is again, dominant in the exhibition, and an ineluctable form of art in Victorian England. This art of the day is represented well in Abraham Solomon’s monolithic “Departure of the Diligence” (1862). This noisy and haphazard street scene is cluttered with a carriage, people looking at their watches, travel trunks, women holding babies, watchers leaning out their window, strangers in an ally. A painting of such candid, lucid, and poignant reality is a descendant of the Dutch and Flemish flair for the genre, evident most clearly in Brueghel.

The Victorians were also strongly influenced by the Romantic tradition. Like Constable or later, Turner, the romantic subjects focused on nature or exotic locations where the mind is left to its own devices, left to contemplate, to wonder. The Holloway show has many landscapes, images of nature or distant locations such as Turkey, Egypt or Jerusalem. Either was subject matter for Romantic artists who, it might be conjectured, sought locations not yet victim to industrialization. The many landscapes that are shown in the collection range from seascapes to dusty streets of the orient and majestic mountain ranges. In philosophy, Burke spoke of the timelessness and temporality of beauty and the infinite of the sublime. In the works of Ruskin he professed the picturesque as the ultimate visual aesthetic, thus leading to an English style still popular today.

One particularly striking painting in the show which puts England’s Romanticism on par with the Germans’ or the French is Clarkson Stanfield’s 1875 “View of the Picudu Midi d’Ossau in the Pyrenees with Brigands.”|

The large painting is shaped like a Gothic altarpiece whose pointed arch is accentuated by the supernatural mountain peak lifting the eye and the soul upward. The painting, like those of many of the Romantics, is contrived to bring out a sublime sense, and although the painting’s title points to an actual locale, the scene seems otherworldly, its peaks and clouds, mists and valleys alluding to the sublime, that sensibility sought by so many of the Romantics.

As befits an era lodged between the Romantic past and the modern future, the Victorian age overflowed with content. No wonder, then, that these paintings are weighty not only in size but in subject matter and content. Most importantly they represent Victorian mentality, a century that fascinates and intrigues those whose interest in history is piqued by a symphony of cultural, political, and social manifestations through the visual arts.

BYU MOA through Oct. 24. 801-422-8287. www.moa.byu.edu/ Amission Free

Ehren Clark studied art history at both the University of Utah and the University of Reading in the UK. For a decade he lived in Salt Lake City and worked as a professional writer until his untimely death in 2017.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts