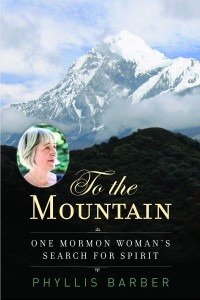

To the Mountain: One Mormon Woman’s Search for Spirit

(Quest Books, 2014))

By Phyllis Barber

Reviewed by Jake Clayson

Given the chance to read Phyllis Barber’s To the Mountain: One Mormon Woman’s Search for Spirit before I served as a Mormon missionary on the Saddle Lake Indian Reservation in Alberta, Canada, I might have had the sense to learn something when a Cree man told me about Manitou. Since I didn’t, all I remember is this: as we stood in parallel dusty ruts in front of his home, he pointed up and said “glitche manitou: great spirit,” then pointed down at a beetle crawling between our feet and said “manidoon: little spirit. Both names come from the same word: Manitou. That’s the life force within all creation. It’s what makes everything sacred.”

Given the chance to read Phyllis Barber’s To the Mountain: One Mormon Woman’s Search for Spirit before I served as a Mormon missionary on the Saddle Lake Indian Reservation in Alberta, Canada, I might have had the sense to learn something when a Cree man told me about Manitou. Since I didn’t, all I remember is this: as we stood in parallel dusty ruts in front of his home, he pointed up and said “glitche manitou: great spirit,” then pointed down at a beetle crawling between our feet and said “manidoon: little spirit. Both names come from the same word: Manitou. That’s the life force within all creation. It’s what makes everything sacred.”

I heard his words well enough to recount them here, but I wasn’t listening to understand. And I only remembered his affirmation that all life is sacred so I could hold it as an ironic counterpoint against another memory from Saddle Lake: one where two teen-age Cree boys exploded from their front door with loaded rifles, shot a fawn as it ran through their yard, then left its carcass to rot in the sun while they watched MTV. Witnessing violence against nature, and hearing regular reports of shootings and domestic violence on the reservation, I had become cynical about Native spirituality. So I listened impatiently to this talk of Manitou, then moved on to the business of evangelizing to keep from rolling my eyes.

This is clearly not how Phyllis Barber listens. In To the Mountain, her most recent collection of personal essays, Barber recounts a series of spiritual experiences and pilgrimages spanning her 20-year hiatus from Mormonism. Whether these essays find her studying under South American shamans or Tibetan Buddhist monks, worshiping in mega-churches and charismatic Christian congregations, singing with Southern Baptists, or traveling with goddess worshipers in the Yucatan, Barber humbly listens and questions, charitably observes inconsistencies between professed and lived theology as they appear, then meditates upon the whole of each experience to uncover insights and course corrections for her own spiritual walk towards divinity.

While the narrative arc of To the Mountain follows Barber back into Mormonism, it does not function in parallel to the prodigal son parable. Barber does share some elements of her “walk away from Mormonism” in a confessional mode, but she views the majority of her experiences on that walk as steps toward divinity, not transgressions against it. Moreover, each time To the Mountain engages Mormonism–including those passages that affirm and explore her current relationship with the faith and culture she was raised in–the relationship is thoughtfully and sensitively negotiated. Though she admits that part of her longs to tell some Latter-day Saints what they want to hear, i.e., that she has returned because “Mormonism is the purest path to the truth and to God’s presence,” she still openly objects to a number of policies, practices, and theological paradigms; the reasons she offers for her return are more nuanced.

Which is to say that To the Mountain is not the work of a writer who receives any theology with unquestioning acceptance. Rather, Barber’s essays are a product of a mind compelled by a persistent creative tension between credulity and skepticism. In one essay, as she describes herself journaling about an experience in an ancient Mayan temple among goddess worshipers, Barber interrupts her own rhapsodic account:

And yet… I stopped writing, suddenly aware that there was always an “and yet” in everything to do with me, always a lead out of the present moment to consider the “real” nature of things. How much of this was imagination? How much was hyperbole?

I found this self-awareness very refreshing. Often, just as my brow began to furrow, just as I was ready to say, “Come on, Phyllis. Aren’t you getting a little carried away?” she would shift her meditative gaze toward some complicating counterpoint, leaving little room to doubt that she is a woman with both her head and heart in the game.

Barber’s eagerness to find and embrace truth wherever she finds it, coupled with her persistent habit of self-reflective cross-examination, assures us that she is far more concerned with seeking divinity than proving doctrine or disseminating wisdom. “It is not my wish to establish an imperious throne on which I can sit and toss beads, strands and crystals of wisdom to the masses,” she affirms early on. This largely explains why To the Mountain is so disarming and inclusive; whether or not we fully agree with her religious views or embrace her explanation of spiritual phenomena becomes a moot point in light of her theological egalitarianism.

And this is what I wish I could have learned before I became a missionary, before I silently scoffed at Manitou; if I had been in search of Spirit, that “feeling of being in a river-like flow that carries all of us forward”–the way Phyllis Barber is throughout To the Mountain–I might have had ears to hear when the Cree concept of Manitou was shared with me. I might have understood something more of the Light of Christ as described by Mormonism.

Reflecting on it now, I realize that I’ve typically thought of that light which “proceedeth forth from the presence of God” as little more than a spiritual pre-school teacher, a Jiminy Cricket for those who haven’t received the gift of the Holy Ghost through priesthood ordinance. But thinking of the Light of Christ, “which is in all things, which giveth life to all things, which is the law by which all things are governed,” as Manitou, I feel at once chastened and honored. Maybe I’ve underestimated the role and import of a divine gift given to elevate and unify all creation.

Whatever the case may be, Phyllis Barber’s To the Mountain echoes and illustrates words spoken by Mormon apologist Terryl Givens in the 2007 FairMormon conference: “Other traditions have much to teach us. Not by way of confirming, corroborating, or verifying the truths we already have. But by way of actually adding to the body of revealed doctrine we call precious and true.”

As it enacts Givens’ ideal, To the Mountain is an invitation to all spirit seekers–Mormon or not–to become more teachable, charitable and curious in the presence of the other; to search for divinity everywhere and in everyone.

#

Phyllis Barber is the author of eight books, including a trilogy of memoir: How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir (a coming-of-age story that won the Associated Writing Program Award for Creative Nonfiction in 1991 and the Association of Mormon Letters Award in Biography in 1993); Raw Edges, a coming-of-age-in-middle-age story; and To the Mountain: One Mormon Woman’s Search for Spirit. She is the mother of four sons, a founder of the Writers at Work Conference, and a teacher in the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in Writing Program for many years.

Phyllis Barber is the author of eight books, including a trilogy of memoir: How I Got Cultured: A Nevada Memoir (a coming-of-age story that won the Associated Writing Program Award for Creative Nonfiction in 1991 and the Association of Mormon Letters Award in Biography in 1993); Raw Edges, a coming-of-age-in-middle-age story; and To the Mountain: One Mormon Woman’s Search for Spirit. She is the mother of four sons, a founder of the Writers at Work Conference, and a teacher in the Vermont College of Fine Arts MFA in Writing Program for many years.

Jake Clayson is currently an MFA student at Brigham Young University studying creative nonfiction in the tradition of Montaigne. His creative thesis, These Stones Will Shout, is a collection of personal essays exploring instances where the work of theologians, philosophers, and secular rock & roll icons intersect. He lives with his wife and three kids in Mapleton, Utah.

Categories: Book Reviews | Literary Arts

Excellent, sensitive review of my most recent book. Would that all writers had such a thoughtful reviewer as Jake Clayson,

This is an insightful, superb review of an insightful, superb book. All of Barber’s books make me want to be a better writer, seeker, and thinker. I loved taking this journey with her to the mountain.