Artists make art for rich people. Well, maybe not for them, but it’s the well-to-do and the institutions they govern who buy art. If that statement is an oversimplification, there’s a basic economic truth at its core: most of the people artists know can’t afford their work (for that matter, most artists can’t afford their own work). It’s a truth that gnaws at many artists. Individually, they deal with it with the family and friends’ discounts, the generous gifts at holiday time (“Hey, I got you a sweater.” “Hey, a I got you an original work of art.”). But that’s not enough for some, like artist and Nox Contemporary gallery owner John Sproul, who founded and directed the Foster Art Program (2009-2011), where patrons were able to live with an original work for a certain period of time, free of charge. It was partly about expanding people’s appreciation of art to include contemporary idioms, but also addressed the economic obstacle (see here). In a similar vein, Artists of Utah at one time toyed with the idea of an online platform that would connect artists with professionals and tradespeople interested in trading for their work: think of it as Tinder for artists and art lovers (like many good ideas, it’s still unrealized). And now there’s Art in the Home, an exhibit at Rio Gallery that showcases a new initiative by Salt Lake Valley artist Clinton Whiting to put art in the homes of those who can’t afford it.

“The concept is to get original artwork in the homes where it can be greatly appreciated by those who would have a difficult time acquiring it,” says Whiting. And 14 Utah artists participated, an eclectic group with no specific stylistic bent: figurative and landscape paintings, sculpture, abstract and non-referential works were all included in the online and physical catalog of works participants were able to choose from. “I’ve been carrying the physical catalogs around with me for the past five months,” Whiting says on the eve of the exhibition. “I’ve asked strangers and people I know and then if they weren’t interested, I asked them if they knew anyone who would be interested.” He found many reluctant to accept free art. “I imagine for a lot of people it was a trust issue. I imagine them asking themselves, ‘What’s the catch?’ ‘What does this guy really want?’”

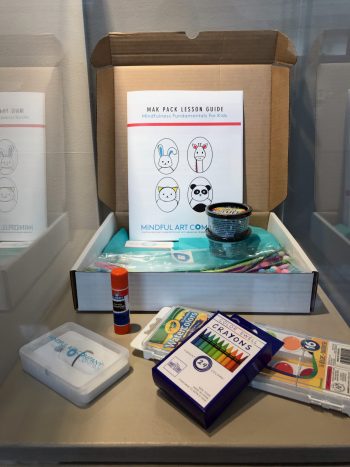

One catch was the participants were asked to give an object from their home in return. These objects, on display at the Rio along with the art, were an even more eclectic mix than the artistic styles: a book, a skateboard, an antique clock, an old map, a family photograph, an old textbook, all of these were exchanged for works of art. Most of the participating artists still don’t know what they have received, but Paige Anderson dropped into the Rio with her daughters this week to pick up her painting from the previous exhibition, the Statewide Annual, and saw that one of her paintings was exchanged for a ‘meditation kit.’ “My oldest daughter can’t wait for this show to come down and try it out. The person who traded for this piece wrote about their experience with it and what they said really touched me: they mentioned not owning abstract art and not really appreciating it before, but this piece has opened their eyes to the intricacies and the work behind it. They said they immediately knew they wanted to trade for something they had worked hard on and the meditation kits they make sprung to mind.”

No requirements, financial or otherwise, were put on the exchanged objects, but Whiting says many participants opted to trade something of value, if only sentimental. Sure, a bottle of Inca Cola might have real cane sugar instead of corn syrup, but it still seems hardly a fair trade for Stephanie Hock’s urbanscape . . . until you learn it was the only souvenir the participant retained from their monthlong trip to Peru during high school, their first time out of the country.

Another participant traded a pair of touring skis, not for their monetary value (yes, skis are expensive) but for their sentimental value. “Skiing is a big part of my life, and backcountry skiing specifically enhanced that experience for me dramatically. Touring to me is freedom. Skiing outside of bounds you get to travel wherever you are willing to physically push yourself to go. Because the risks incurred are higher, you naturally observe and learn so much more about the mountains we are surrounded by. Quite frankly, these have nothing in common with the painting I chose! But I will always look at that painting and think of how, in a really spontaneous way, my two passions: art and skiing, were directly connected. That’s pretty cool.”

These responses come from the second catch — a survey the participants were asked to fill out after living with the pieces for the first month, asking them about the object they exchanged, how the artwork has affected them and their overall thoughts on the project. One participant, having recently gone through a divorce, says the painting she received was the death knell for a hand-me-down futon. “Seeing that painting next to a futon was the final straw I needed. My whole living room looks better. I got a new couch, which is still a hand me down, but looks nicer and is more comfortable. If it weren’t for the painting I would have just left the futon there.” Others spoke of the works bringing peace into their homes, or a new creative energy to their lives.

Thanks to Duchamp, we’ve become accustomed to viewing found objects as art when they become recontextualized in a gallery or museum setting, so a viewer may be forgiven if at the Rio exhibit they find themselves as entranced by the household objects on display as by the art (seeing the former on pedestals and behind vitrines helps with the whole “aura” thing). Delve into some of the survey responses and you may find the distinction between the two types of objects on display fading: one participant’s purposeful selection of her late father’s high school car club sweater, in exchange for a hand-stitched heart by Hilary Jacobsen, has as much intent and meaning as many artist statements.

Thanks to Duchamp, we’ve become accustomed to viewing found objects as art when they become recontextualized in a gallery or museum setting, so a viewer may be forgiven if at the Rio exhibit they find themselves as entranced by the household objects on display as by the art (seeing the former on pedestals and behind vitrines helps with the whole “aura” thing). Delve into some of the survey responses and you may find the distinction between the two types of objects on display fading: one participant’s purposeful selection of her late father’s high school car club sweater, in exchange for a hand-stitched heart by Hilary Jacobsen, has as much intent and meaning as many artist statements.

The final survey question about the project in general generated enthusiastic and grateful responses from most participants so, Whiting says, in one form or another the project will continue. He has been invited to try something similar in Sanpete County and hold another exhibition at The Granary in Ephraim. Along the way, he’ll be thinking of tweaks. “I would like to try a version targeted at people who can afford original art but choose to spend their money on other things. And what value would they put on original art? I think the key to this project is ‘value’; what do we value and why.”

Art in the Home, Rio Gallery, Salt Lake City, through March 9.

The founder of Artists of Utah and editor of its online magazine, 15 Bytes, Shawn Rossiter has undergraduate degrees in English, French and Italian Literature and studied Comparative Literature in graduate school before pursuing a career in art.

Categories: Artist Profiles | Visual Arts