[dropcap]Almost[/dropcap] from the beginning, Diane Stewart’s Modern West Fine Art has been evolving away from the cowboys, American Indians and Western landscapes — however jazzed up or modernized — that threatened to define it at its inception. Gradual at first, the process has picked up steam in recent months, with the notable exhibition, in March, of Taos Modernists Beatrice Mandelman and Louis Ribak, followed by the current exhibit, West: The Effect of Land and Space. In the latter, which features work by 11 artists, some new to the gallery and others old hands, you will find an image of a cowgirl boot; and there’s a landscape arch straight out of a national park brochure; but these tropes are the exceptions rather than the rule in an exhibition that focuses as much on the “modern” as the “West” of the gallery’s moniker.

[dropcap]Almost[/dropcap] from the beginning, Diane Stewart’s Modern West Fine Art has been evolving away from the cowboys, American Indians and Western landscapes — however jazzed up or modernized — that threatened to define it at its inception. Gradual at first, the process has picked up steam in recent months, with the notable exhibition, in March, of Taos Modernists Beatrice Mandelman and Louis Ribak, followed by the current exhibit, West: The Effect of Land and Space. In the latter, which features work by 11 artists, some new to the gallery and others old hands, you will find an image of a cowgirl boot; and there’s a landscape arch straight out of a national park brochure; but these tropes are the exceptions rather than the rule in an exhibition that focuses as much on the “modern” as the “West” of the gallery’s moniker.

Gallery director Shalee Cooper, who came on board two years ago, was responsible for working with the Mandelman-Ribak Foundation to stage the recent exhibition on the pair of postwar abstractionists, and she decided to have Mandelman’s works re-emerge in West, where they continue to feel fresh and worthy of renewed scrutiny as they mingle with those of the other artists. Cooper says the flow of the current show — more than two dozen 2-D works along with a sprinkling of ceramics by Suzanne Hill and Courtney Leonard — is due in large part to the influence of Liberty Blake, who was brought on this summer as curator and whose influence, Cooper says, can be seen in the way pieces communicate with and play off each other, much like the paper elements in Blake’s own collages. In these conversations, the visual aspects of our Western landscape crop up, but the exhibit shows that when we talk of the West, we are speaking not just about certain longitudes, but about ideas: space, solitude, freedom, discovery.

Like many before her, Al Denyer came west from England, via the Midwest, and the sense of space she found here has shaped her art ever since. For the past decade, her work has been characterized by delicately rendered, monochromatic drawings that evoke topographic maps and satellite views of expansive landscapes. Denyer’s interest in the land has continued to expand, to include the North, in Alaska, and the Far East, in Siberia, always taking a vantage point outside the human to see — and so conceive of — the world in a new way. Similar to previous bodies of work, the lines in Denyer’s “Strata” and “Stratify” series on view here can read equally well in the macro — as some untouched mountain range seen from the stratosphere — as in the micro— the skin of man or beast viewed under a microscope. But these recent works also have taken on an undulating quality, so that the vast expanse of the ocean comes to mind as well.

Like many before her, Al Denyer came west from England, via the Midwest, and the sense of space she found here has shaped her art ever since. For the past decade, her work has been characterized by delicately rendered, monochromatic drawings that evoke topographic maps and satellite views of expansive landscapes. Denyer’s interest in the land has continued to expand, to include the North, in Alaska, and the Far East, in Siberia, always taking a vantage point outside the human to see — and so conceive of — the world in a new way. Similar to previous bodies of work, the lines in Denyer’s “Strata” and “Stratify” series on view here can read equally well in the macro — as some untouched mountain range seen from the stratosphere — as in the micro— the skin of man or beast viewed under a microscope. But these recent works also have taken on an undulating quality, so that the vast expanse of the ocean comes to mind as well.

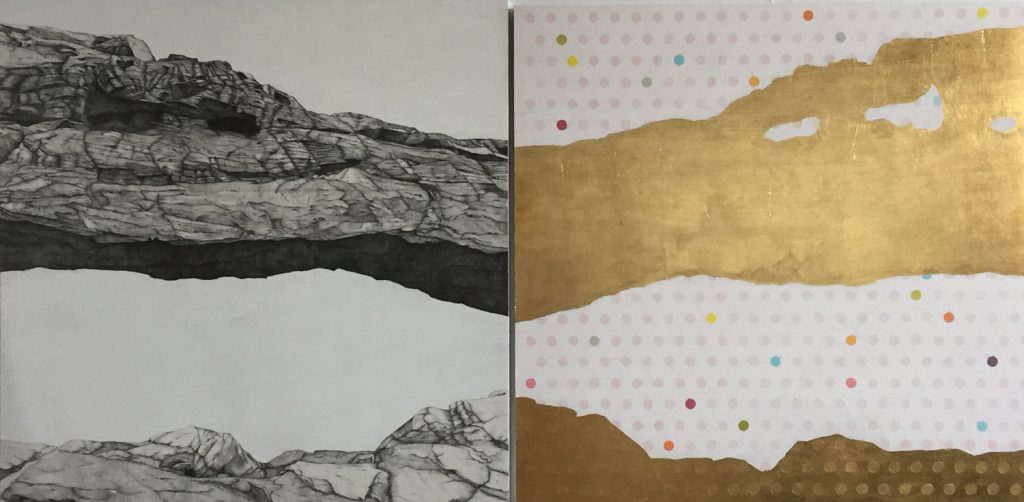

Kiki Gaffney is another artist who discovered the Western landscape as an adult. An East Coast girl, she first visited Utah in 2003, with her future husband and Utah native, artist Tom Judd, and found the vistas here “utterly breathtaking.” The spires and arches she renders in graphite (with a delicate line resembling Denyer’s) are of the sort captured by any number of tourists with their smartphones. But Gaffney pairs these drawings with a second work, where the eroded rock is transformed by paint and gold leaf into something else, so that what could be a tired cliché becomes fodder for aesthetic alchemy in the artist’s Pennsylvania studio.

In contrast to these newcomers, Rebecca Campbell is a native of the West, a Utahn who now lives and works in California. In her painting “Returning Home From Home” there’s nothing “breathtaking” about the dry grass and low-slung mountains depicted: it’s the type of landscape that in the southern half of the state flanks I-15 on the west and goes largely unremarked. These might be the Pahvant or the Tushar mountains, two ranges most Utahns wouldn’t be able to name; but they would be visually familiar to anyone who has repeated that north-south trip between the Wasatch Front and St. George, the sort of details, amplified here by palette and brush stroke, that for the native can invoke a sense of return (or departure), the land being a catalyst for nostalgia as much as for discovery.

Where the newcomer’s bias may be to the farsighted, swallowing in new horizon lines and grand vistas, the native might lean toward the intimate aspects of a setting, showing that the sense of a landscape can be defined as much by a slight shift in flora or fauna as it is by any grand geologic upheavals. Salt Lake City native Jody Plant knows the West, and especially her immediate surroundings, well. The former librarian sees the landscape with a poet’s eyes (Tennyson was famously shortsighted) and in these current works looks for small details, like the backyard ornithologist counting the number of quail from year to year, or the bibliophile who enjoys watching how a book ages, both physically and psychologically. Like a magpie, she assembles bits and pieces of found objects with evocative scraps of text to create nests that allow the influence of the land and the transformation of time to merge.

Where the newcomer’s bias may be to the farsighted, swallowing in new horizon lines and grand vistas, the native might lean toward the intimate aspects of a setting, showing that the sense of a landscape can be defined as much by a slight shift in flora or fauna as it is by any grand geologic upheavals. Salt Lake City native Jody Plant knows the West, and especially her immediate surroundings, well. The former librarian sees the landscape with a poet’s eyes (Tennyson was famously shortsighted) and in these current works looks for small details, like the backyard ornithologist counting the number of quail from year to year, or the bibliophile who enjoys watching how a book ages, both physically and psychologically. Like a magpie, she assembles bits and pieces of found objects with evocative scraps of text to create nests that allow the influence of the land and the transformation of time to merge.

Petecia Le Fawnhawk shares Plant’s attention to detail and fondness for the found natural object. She works in sculpture and video installation as well as land art, but is represented in West by a series of graphite drawings in which wood, bone and stone are elevated to the status of icons. Placed on a plain white background, and executed with such detail that one can almost feel the texture scrape across one’s skin, they take on a spiritual quality that invites reverence and contemplation.

Le Fawnhawk’s minimal quality is shared by Shalee Cooper, whose works are shown at the gallery for the first time. Cooper is best known as a photographer — her role in Utah’s photographic circles has been longstanding and influential — but with her debut at Modern West she expands her media so that you’ll find two bodies of related work in the gallery: a series of black-and-white gelatin silver photograms, shown together, and a number of black-and-buff works of black gesso on unprimed canvas spread out among that of the other artists. Befitting the work of a photographer, both series play with the idea of the positive and the negative. In the photograms, the ambiguity between the two is more pronounced: “Three Sisters Two Brothers” calls to mind the names of forms in a place like Arches National Park, and you can see both the trio and the pair, but like the optical illusion of the goblet and the two faces, not at the same time. The canvases, with simple but powerfully arranged forms, tend to be less ambiguous, but similarly rely on binary dynamics, in works with titles like “Light and Dark,” “Sky and Land,” “Me and You.”

Le Fawnhawk’s minimal quality is shared by Shalee Cooper, whose works are shown at the gallery for the first time. Cooper is best known as a photographer — her role in Utah’s photographic circles has been longstanding and influential — but with her debut at Modern West she expands her media so that you’ll find two bodies of related work in the gallery: a series of black-and-white gelatin silver photograms, shown together, and a number of black-and-buff works of black gesso on unprimed canvas spread out among that of the other artists. Befitting the work of a photographer, both series play with the idea of the positive and the negative. In the photograms, the ambiguity between the two is more pronounced: “Three Sisters Two Brothers” calls to mind the names of forms in a place like Arches National Park, and you can see both the trio and the pair, but like the optical illusion of the goblet and the two faces, not at the same time. The canvases, with simple but powerfully arranged forms, tend to be less ambiguous, but similarly rely on binary dynamics, in works with titles like “Light and Dark,” “Sky and Land,” “Me and You.”

Liberty Blake’s work is also new to Modern West. Her work in collage has been defined by the straight (or nearly straight) line, scraps of paper forming juxtaposed rectangles and polygons in compositions that rely on intricate balances and small visual flourishes for their success. In recent works, some of which appear here, circles and ovals have emerged, usually as smaller ornamental devices, contained by one of her rectangular masses. But in “Yellow and onto the South Rim – Gooseberry Mesa,” she has indulged her newfound delight in curves, allowing two beige forms to expand and take center stage. The sense one gets, in her work, of the landscape as if seen from an aerial perspective, is transformed in this piece, as the arranged paper suggests the form of two large boulders, seen straight on against a blue sky; but this tendency for the work to lapse into a traditional landscape view is adeptly kept in check by a sliver of green, that Jules Olitski would appreciate, in the upper left corner.

Liberty Blake’s work is also new to Modern West. Her work in collage has been defined by the straight (or nearly straight) line, scraps of paper forming juxtaposed rectangles and polygons in compositions that rely on intricate balances and small visual flourishes for their success. In recent works, some of which appear here, circles and ovals have emerged, usually as smaller ornamental devices, contained by one of her rectangular masses. But in “Yellow and onto the South Rim – Gooseberry Mesa,” she has indulged her newfound delight in curves, allowing two beige forms to expand and take center stage. The sense one gets, in her work, of the landscape as if seen from an aerial perspective, is transformed in this piece, as the arranged paper suggests the form of two large boulders, seen straight on against a blue sky; but this tendency for the work to lapse into a traditional landscape view is adeptly kept in check by a sliver of green, that Jules Olitski would appreciate, in the upper left corner.

The title of Blake’s piece refers to a mountain bike trail in southern Utah, and mountain bikers, along with derby girls and hipsters, are among the characters of Jann Haworth’s vision of the modern myth of the West. She’s still in love with the trappings of the Hollywood version (hence the aforementioned cowgirl boots), but has turned her eye, and hand, to celebrating these new protagonists as well. Actually, it’s their costumes she portrays — rendered in finely handled pastel, a medium that seems to blend her Pop aesthetic with more classical artists like Watteau and Fragonard. The figures, not unlike those in her mannequin series, remain colorless line drawings. Combine these with titles of other works — like “Ceci n’est pas un Magritte” and “Paper Moon” — suggesting the illusory nature of appearance, and one gets the sense that Haworth, to borrow a phrase, would have us be in the myth but not of the myth.

The title of Blake’s piece refers to a mountain bike trail in southern Utah, and mountain bikers, along with derby girls and hipsters, are among the characters of Jann Haworth’s vision of the modern myth of the West. She’s still in love with the trappings of the Hollywood version (hence the aforementioned cowgirl boots), but has turned her eye, and hand, to celebrating these new protagonists as well. Actually, it’s their costumes she portrays — rendered in finely handled pastel, a medium that seems to blend her Pop aesthetic with more classical artists like Watteau and Fragonard. The figures, not unlike those in her mannequin series, remain colorless line drawings. Combine these with titles of other works — like “Ceci n’est pas un Magritte” and “Paper Moon” — suggesting the illusory nature of appearance, and one gets the sense that Haworth, to borrow a phrase, would have us be in the myth but not of the myth.

To the attentive reader who has noticed the use of feminine pronouns, yes the artists in West are all female (the Gorilla Girls would be proud — a gallery owned, directed and curated by powerful and creative women, showing vibrant work by female artists). For those who may fear (or for those who were hoping) the matriarchy has taken over and outlawed the Y chromosome, note that West will be followed by an exhibition of works by John Berry, an artist who has gone through a transformation not unlike the gallery’s: he began his career painting landscapes of the desert West in the tradition of artists like Maynard Dixon, but now works in a nonobjective manner. Nor has the gallery completely forgotten its roots, with exhibitions planned this fall featuring works by Michael Coles, who lives in Montana and primarily photographs the American West, and Navajo artist Patrick Hubbell. In the meantime, West deserves a visit, to catch some snippets of the dialogues going on between these works, and as a primer for what one hopes the gallery will allow to become a series of soliloquies in the near future.

West – The Effect of Land and Space, Modern West Fine Art, Salt Lake City, through September 15.

The founder of Artists of Utah and editor of its online magazine, 15 Bytes, Shawn Rossiter has undergraduate degrees in English, French and Italian Literature and studied Comparative Literature in graduate school before pursuing a career in art.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts

Thank you for such a comprehensive and thoughtful review. Shawn really captures the essence of our current show…. “West – The Effect of Land and Space”. Thank you for so eloquently describing our artists’ process and inspiration…..and also the subtle, but impacting redirecting of our aesthetic and mission.

Not a moment too soon, women are abandoning the quest to be “as good as men” (at what men do) and sharing with each other (and those men smart enough to join in as witnesses) what they can do: smart, insightful, fresh, original, welcome works of imagination and fact. Since art is always best when it’s new, when anything goes and rules, instead of needing breaking have yet to be made, this is the moment to look closely and, if so inclined, to collect what will be the foundation of a new “new.”

Note: too much of the signature of our time is the cry of the dying: “The world is coming to an end!” True enough if you’re a sexist male, a racist, a whitemale entrepreneur. Modern West can show us what will be left when the dinosaurs are gone, and it’s cause to keep on keeping on.