Ever think you might be killing the thing you love by telling people about it? That if you let all the high rollers at Deer Valley and all the ski snobs with Alta passes know how great Brighton is (because the night skiing extends the season by a third) pretty soon the runs on top of Big Cottonwood Canyon will be filled with bad skiers in overpriced equipment or the lift lines clogged with skittish patrons afraid to get cooties from a snowboarder? Or that if you write a passionate article about the magical solitude to be found hiking S___________ Canyon, you’ll soon become a grumbling misanthrope rather than a contented Taoist with your own little happy place? Something similar probably happens to all those landscape painters and backcountry photographers who celebrate the majesty of our national parks and monuments: they’ve done such a good job, we’re now considering a ticketed system for entering Arches.

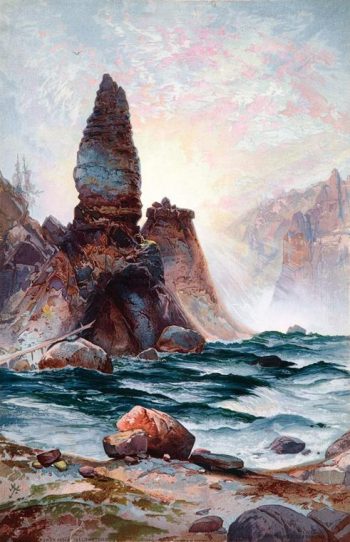

On the other hand, had writers and painters not described and depicted the natural wonders to be found in places like Yellowstone and Yosemite, Zions and Canyonlands, those places might now be filled with oil rigs and timber companies. When the young American nation flexed its muscles westward, it was interested in very American things, like science and commerce, but the public was also fascinated by stories of exotic lands. And when artists tagged along with expeditions into the country’s undiscovered reaches, serving as documentarians, they also became publicists for lands marked by physical wonders and majestic light. The grand paintings by Hudson River School painters like Thomas Moran captivated, even while they could be suspected of hyperbole; but the 1871 photographs of Yellowstone by William H. Jackson convinced Americans that this land of wonder was the real deal. And the National Park System—which currently protects and manages 59 parks and 300 monuments—was born.

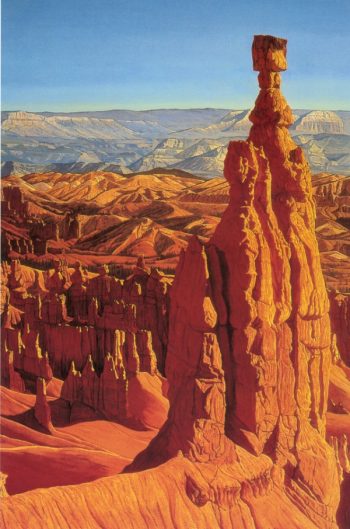

Pulled mainly from collections within our state, Brigham Young University Museum of Art’s Capturing the Canyons: Artists in the National Parks highlights the artistic celebration of the parks within Utah — Zion, Arches, Capitol Reef, Canyonlands — but also features work by artists like Moran and Jackson from nearby parks like Grand Canyon, Yellowstone and Yosemite, which serve to establish and fill out the story of the National Park System.

It’s no surprise that the park system was born within the decade after 1869, when the continent was united by the intercontinental railroad, and spurs to all points of the compass brought access to natural resources as well as natural wonders. When Albert Bierstadt first visited Yosemite in 1863 the trip took him several weeks, by train, stagecoach and horse, but in 1871 the same trip, all on rails, took him six days. Gilded-age wealth brought the desire for adventure and tourism, and artists’ images of places like Yosemite Valley and the activism of people like John Muir helped preserve these places (so that tourists soon could flood them and ruin the views).

Though Utah is now known for its national parks— it’s at the heart of the Grand Circle Tour that attracts millions every year— they were rather late in coming. Thomas Moran helped popularize Yellowstone for the magazine-reading public with his wonderfully detailed chromolithographs, a number of which are on exhibit at BYU. He tried to do the same for Zion Canyon, which he visited in 1873 with a John Wesley Powell expedition (his sketchbook from that trip is on display). In 1876 he created the chromolithograph “The Valley of the Babbling Waters,” a composite of beautiful perspectives in what is now Zion National Park. It was the same year Utah artist Alfred Lambourne’s “Temples of the Rio Virgin,” which opens Capturing the Canyons, was exhibited at America’s Centennial World’s Fair in Philadelphia. Lambourne’s technique is not as accomplished as that of Moran, whom he idolized, but his majestic view of a lone fisherman bathed in twilight beneath majestic cliffs exposed a national audience to the spectacular scenery in Utah’s southwest corner. It wasn’t until 1919, however, that the area was declared a national park. Infrastructure soon followed, especially during the WPA years of the Great Depression, and numerous artists began visiting the park. Bryce followed a decade later, but Canyonlands (‘64) Capitol Reef and Arches (‘71) were all designated within the past generation.

Utah artists abound in this exhibit. Lynn Fausset, J.B. Fairbanks, LeConte Stewart, Lewis Ramsey, Ranch Kimball and Mabel Frazier are all here. As are later, more modern artists like Doug Snow and Lee Deffebach, and living artists like Mark Knudsen. And none of the works are tough to look at: it’s really hard to miss the artistic mark when the colors and forms of your subjects are so dynamic. Lambourne’s friend and colleague H.L.A. Culmer was a great adventurer—he was one of the first to climb Sierra Point in Yosemite, and also one of the first to paint the Alaskan interior and Utah’s natural bridges—and his traveling sketchbooks of detailed yet economic watercolors are a joy, despite their size and preliminary nature.

Three works in the exhibit were provided by David Dee Fine Art: a view of Zion’s Watchman by Franz Bischoff, James Everett Stuart’s oil painting of geysers in Yellowstone, and Frederick Dellenbaugh’s small painting of Grand Canyon; and the Salt Lake City gallery has hung their own show, National Parks of the West, to coincide with the BYU exhibit (they’ve added Glacier National Park to their list of locales). There’s a Moran chromolithograph of the Grand Canyon (which would have fit nicely with the others at BYU) that manages to look down past multiple planes of rocks, toward the water at the bottom of the canyon, as well as upward toward the clouds. Thomas Hill’s view of Yellowstone geysers seems like a companion piece to Stuart’s: both are a bit clumsy and include figures in the landscape to give scale to the erupting geysers. Hiroshi Yoshida’s 1925 woodblock print of the Grand Canyon is a wonderfully delicate winter scene, and an indication of the park’s early international draw (surprisingly the Grand Canyon was only named a park in 1919). The Swedish painter Gunnar Widforss is represented by two detailed watercolors of the Grand Canyon that capture the effects of aerial perspective that abounds at the site, as well as a painting of Angel’s Landing in Zion whose brilliance has unfortunately faded. These delicate works are in sharp contrast to those of painter Conrad Buff. Though his locations are unspecified, one imagines they are in a national monument, or should be. In bright, flat colors that eschew the perspective studies that dominated early scenes of these places, he creates works where one can almost feel the cool air rising from the deeply shaded canyon walls.

Three works in the exhibit were provided by David Dee Fine Art: a view of Zion’s Watchman by Franz Bischoff, James Everett Stuart’s oil painting of geysers in Yellowstone, and Frederick Dellenbaugh’s small painting of Grand Canyon; and the Salt Lake City gallery has hung their own show, National Parks of the West, to coincide with the BYU exhibit (they’ve added Glacier National Park to their list of locales). There’s a Moran chromolithograph of the Grand Canyon (which would have fit nicely with the others at BYU) that manages to look down past multiple planes of rocks, toward the water at the bottom of the canyon, as well as upward toward the clouds. Thomas Hill’s view of Yellowstone geysers seems like a companion piece to Stuart’s: both are a bit clumsy and include figures in the landscape to give scale to the erupting geysers. Hiroshi Yoshida’s 1925 woodblock print of the Grand Canyon is a wonderfully delicate winter scene, and an indication of the park’s early international draw (surprisingly the Grand Canyon was only named a park in 1919). The Swedish painter Gunnar Widforss is represented by two detailed watercolors of the Grand Canyon that capture the effects of aerial perspective that abounds at the site, as well as a painting of Angel’s Landing in Zion whose brilliance has unfortunately faded. These delicate works are in sharp contrast to those of painter Conrad Buff. Though his locations are unspecified, one imagines they are in a national monument, or should be. In bright, flat colors that eschew the perspective studies that dominated early scenes of these places, he creates works where one can almost feel the cool air rising from the deeply shaded canyon walls.

What is almost entirely absent from these exhibits is the perspective of the people for whom these lands were ancestral home rather than eye-popping novelty. The National Park System, after all, has largely been a white-man’s affair. Federal policies and attitudes have shifted over the years, but even the increasing inclusion of Native American voices hasn’t been without its obstacles: we currently find native groups on both sides of the controversy over the possible designation of Bears Ears Monument in southeastern Utah. Once again, it’s a double-edged sword that protects these natural landmarks. Without the park system, various sacred spots might have been completely (rather than just partially) ruined by the voracious thrust of Manifest Destiny; but that may be cold comfort to those who see these places as land stolen rather than land protected. And “protected” is a provisionary term. As Navajo photographer Will Wilson’s work “Autoimmune Response #2” reminds us, while we can build a fence around the land, the air is something much harder to protect. And one wonders how many people who flocked to the pristine vistas of Zion or the Grand Canyon in the Cold War era can now only observe the view from the cancer ward.

What is almost entirely absent from these exhibits is the perspective of the people for whom these lands were ancestral home rather than eye-popping novelty. The National Park System, after all, has largely been a white-man’s affair. Federal policies and attitudes have shifted over the years, but even the increasing inclusion of Native American voices hasn’t been without its obstacles: we currently find native groups on both sides of the controversy over the possible designation of Bears Ears Monument in southeastern Utah. Once again, it’s a double-edged sword that protects these natural landmarks. Without the park system, various sacred spots might have been completely (rather than just partially) ruined by the voracious thrust of Manifest Destiny; but that may be cold comfort to those who see these places as land stolen rather than land protected. And “protected” is a provisionary term. As Navajo photographer Will Wilson’s work “Autoimmune Response #2” reminds us, while we can build a fence around the land, the air is something much harder to protect. And one wonders how many people who flocked to the pristine vistas of Zion or the Grand Canyon in the Cold War era can now only observe the view from the cancer ward.

“Capturing the Canyons: Artists in the National Parks,” Brigham Young University Museum of Art, Provo, through Aug.20; “National Parks of the West,” David Dee Fine Arts, Salt Lake City, through June 10.

The founder of Artists of Utah and editor of its online magazine, 15 Bytes, Shawn Rossiter has undergraduate degrees in English, French and Italian Literature and studied Comparative Literature in graduate school before pursuing a career in art.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts

It’s great to see art used as an entry point to a much larger, more crucial topic. I, too, have felt the inhibiting effect of wanting to share a landscape discovery, but not wanting to ruin my discovery in the process. In a brief article that makes several excellent points, the writer brings things to a close in exactly the right place, by asking what we should do about the problem today. Readers should know that there are well-organized campaigns at the state and federal levels to vacate the National Parks, which they may be able to influence with their votes, letters, and donations (hint: the party whose members want to do away with the parks and sell off the lands for development are Republicans). The best point comes last: it’s part of the strategy of the despoilers to return public lands to local control, because locals are more easily subject to manipulation. You only have to fool a few thousand Indigenous Americans into believing that strip mining Bears Ears would improve their lot: not the millions of voters who casually support keeping as much of what remains of the wild country pristine and available to their appreciation.