“Beauty in distress is much the most affecting beauty,” said Edmund Burke in his seminal “Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful.” Burke might have appreciated the work of Chauncey Secrist as few are able: for it is easy to look at Secrist’s work and cast it aside as a derisory, sardonic or dissident body of work when in fact it is a universal critique, an existential examination of theological expression which at root can be positive, and can be, as Burke would recognize, sublimely beautiful.

Secrist was raised in a conservative suburb of Salt Lake City, but not in a religious household; so like many minorities he found himself alienated from the majority. In his early years, Secrist developed a negative attitude towards the dominant belief system, but as he matured, “meeting others from various backgrounds and considering religion from different perspectives,” he came to understand the very personal nature of belief systems. “My main goal with this series,” he says of a body of work currently on exhibit at Salt Lake’s Finch Lane Gallery, “was trying to understand my relationship to religion without being a part of religion, in essence trying to find common ground.”

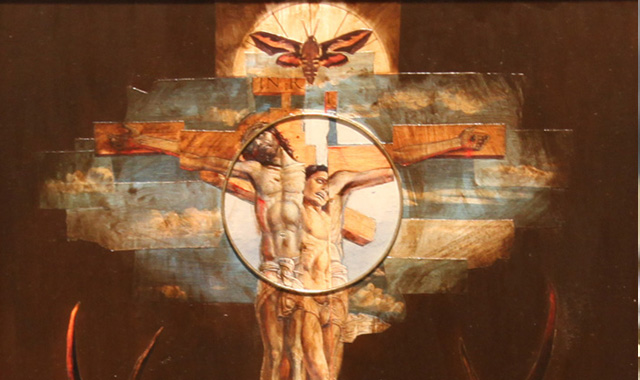

The existential investigation in this series attempts to generate thinking on the level of universals, inspired by particulars, expressed through a myriad iconographic language. Secrist has fought discrimination and learned significant ways and manners of numerous theological expressions and, grounded by a theologically neutral, objective experience, is well equipped with the ability to accurately evaluate a plurality of manifest theological expressions in our culture. Those who choose to look at his work, may glean from his micro-installations both condemnation and approbation, as well as a range of responses in between, representing a mass of quizzical ways and means to investigate a theocratic society that feels very sure of itself. Too sure is the stance of Secrist, in his series of existential, spiritually manifest, metaphorical micro-installations.

One such micro-installation, that at first glance may seem to support establishmentarian Christianity, is more likely charged with visual theological commentary. “A Light Focused Inward Shines Brightest” even sounds resoundingly Christian, but it is loaded with irony. The appropriated card image is a seemingly stalwart Christian male of great physical beauty that apparently stems from inward virtues with features that are Caucasian, European, proto-establishmentarian-Christian. There are even flourishes of what might be wings. Yet this being holds a long golden rod with a very atypically gold fleur de lisat the tip and wears a crown of some mystery with a cryptic halo of distinctive symbolic detail while his robes and shoulder sash are certainly emblematic. From the origins of what Christian sect he emanates is unknown, but of the Pantheon of pagan gods this angelic creature might easily fill in as one of their own.

The metal circle, according to the artist, represents eternity and everything within it, what “shines brightest;” a statement of arbitrariness perhaps? Further, there is a small iron crucifix below, with a skull at the axis. In Art History the skull is a symbol of vanitas, meaning that all life is subject to temporality, as all will pass, thus all is in vain. One might question the authenticity of the source for organized spiritual beliefs, put to examination here; ultimately what is the truth that western civilization has grounded itself upon for 2000 years?

Another micro-installation among many that are existentially questioning is “A Nail in the Mouth of God.” An iron nail overrides the image placed atop a young man, Christ one presumes, with a metal circle next to him, representing, again, eternity. Beneath are the jawbones of a deceased animal pried apart and between is another crucifix, here with the image of Christ upon it. Below is what looks like a rusty old penny. One critique might be that the nail, representing Christ’s death, is the focus for organized Christianity, leaving an absence for the glorification of God the Creator, as the nail is thrust into his gaping jaws. Below is the worthlessness of a truthless world of divine creation in utter chaos.

Be it the equivocal natures of the adoration of Christianity to the dubious structure and the natural order of belief systems, Secrist’s universal message is apparent. These are existential inquiries few are challenging, as theological structures are blindly accepted in a worldly condition that cannot be trusted as a source for truth. These are questions that must be asked of oneself as a source for personal solace and one’s own peace of mind, to inhabit authentically and contentedly within the state of this discordant worldly condition, while maintaining and progressing towards the Greeks’ goal of eudaemonia, or human flourishing.

Ehren Clark studied art history at both the University of Utah and the University of Reading in the UK. For a decade he lived in Salt Lake City and worked as a professional writer until his untimely death in 2017.

Categories: Exhibition Reviews | Visual Arts